Madison, Wisconsin

At various times Wright used the word “aspiration” and “praying hands” to describe the soaring prow of the Meeting Hall.

Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and completed in 1951, when Wright was 84 years old, this church is recognized as one of the world’s most innovative examples of church architecture and one of Wright’s more influential buildings.

Despite being one of the more stunning buildings in Madison it was almost not to be. When the congregation was deciding who should design the meeting hall Wright was not the most obvious or wanted choice. In a widely circulated letter, one society member described Wright as “arrogant, artificial, brazen, cruel, recklessly extravagant, a publicity seeker, an exhibitionist, egotist, sensationalist, impatient, unscrupulous, untrustworthy, erratic and capricious. . . .”

The First Unitarian Society realized (after fees) $102,650 from the sale of its old church and parish house and $23,915 from the sale of its former parsonage. At the winter parish meeting held January 25th, 1946, the vote to hire Wright was twenty-five in favor, three opposed, and one abstention. The building was continually over budget and behind time.

The materials selected by Wright consist of tawny-colored native stone, dolomite, for the masonry, natural finish oak for all of the trim which is a native and plentiful wood in Wisconsin, large expanses of clear glass, placed in horizontal, bands in the two wings and in the prow, and terra-cotta- colored concrete for the exterior steps, patio areas and interior floors.

This was Wright’s “Little Country Church” as it sits on a small hill that once overlooked experimental farms that belonged to the University of Wisconsin.

The benches are designed for multiple uses. They are made of one sheet of 8 X 10 plywood and produced by the apprentices at Taliesin. Plywood was used as a cost-saving material but also makes them light enough to move easily.

Wright was a member of this church and his parents were founding members of the congregation in 1879.

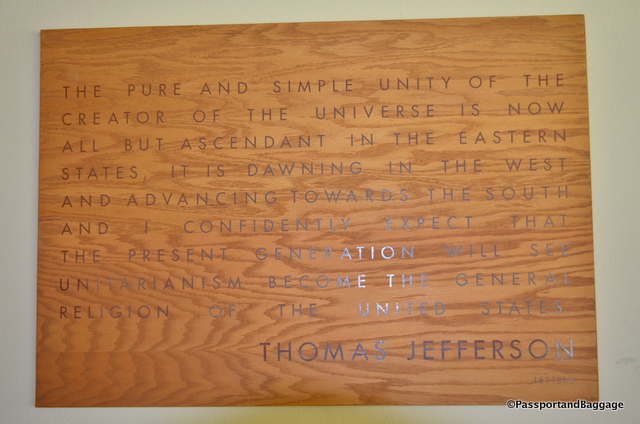

The building reflects Wright’s beliefs in Unitarianism and Transcendentalism. Presumably, to underscore his family’s connection to the church, Wright had the name of his uncle, who was a Unitarian minister, inscribed with the names of five other Unitarian and Transcendentalist on the oak fascia at the base of the octagonal opening in the Hearth Room ceiling. The other names include Charles William Elliot, Theodore Parker, William Ellery Channing, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

*

Unity Chapel also featured a large room divided by a curtain. The Meeting House inscription reads, “Do you have a loaf of bread break the loaf in two and give half for some flowers of the Narcissus for the bread feeds the body indeed but the flowers feed the soul.”

The curtain, which no longer hangs in the hall due to its delicate nature has a wonderful story on its own. In the attempt to cut down on the ever-increasing costs of the building of the church the women of the church took it upon themselves to construct the curtain itself.

Wright agreed to the women’s suggestion for a curtain to hang between the worship space and the social space, but it was to be designed by him. The women, knowing nothing about weaving, took classes at the local college to learn to weave, and then dyed the various materials in their own homes in big vats over their kitchen stoves. Each color was then sent to Wright for his approval.

It is a stunning piece of artwork all unto itself.

Wright’s preliminary drawings reveal his use of a four-foot diamond or quadrilateral parallelogram with 60 and 120-degree angles as the unit grid for the design. The parallelogram provided the basis for the grid Wright used when laying out the floor plans and establishing the elevations for the roof, angular prow, and decorative details.

The Loggia continues the east-west axis and contains offices and a library, which were initially designed as classrooms. The interior walls of the rooms in the Loggia correspond to the angled grid lines incised into the colored concrete floor.

Wright donated these Hiroshige woodblock prints to the church. Each door is bracketed with one horizontal print and one vertical print. When the doors are open, the vertical prints are still completely visible, due to their positioning.

Wright donated these Hiroshige woodblock prints to the church. Each door is bracketed with one horizontal print and one vertical print. When the doors are open, the vertical prints are still completely visible, due to their positioning.

The Loggia ends at the West Living Room. This room was originally intended as the living and dining space of an unbuilt pastor’s residence.

Knowing that the estimates for the construction were well over what the church could afford, arrangements were made with Albert J. Loeser, the owner of a quarry near Prairie du Sac, for the purchase of the dolomite for the walls at $20.00 per cord. Loeser agreed to further reduce prices if the society members hauled the stone themselves. Able-bodied members of the congregation assembled almost every weekend from the fall of 1949 through the spring of 1950 for the sixty-mile round trip to the quarry. It has been estimated that the volunteer stone haulers loaded and then unloaded approximately one thousand tons of stone. The church still refers to this labor force as the “stone haulers”.

This bell was supposed to simply be a decorative piece for the Meeting House. It is made of sheet copper, the same material used in the roof. It was never meant to be rung and was designed to be suspended under the highest point of the roof in front of the glass prow. Strong winds caused the bell to swing so much that it was removed to prevent any more serious damage.