November 29, 2019

Dougga (or Thugga) was a Punic, Numidian and then Roman settlement outside of Tunis by about 2 1/2 hours. The current archaeological site covers 160 acres. UNESCO qualified Dougga as a World Heritage Site in 1997, believing that it represents “the best-preserved Roman small town in North Africa”. The site, which lies in the middle of the countryside, has been protected from the encroachment of modern urbanization, in contrast to Carthage.

Dougga, sitting atop a mountain with excellent access to water was first a Numidian city that existed long before the Romans arrived in Africa. It is possible it came under Carthaginian rule in the 5th century BCE after the 480 BCE Punic defeat when Carthage realized that it needed an empire inland.

Little is actually known of its pre-Roman history. The most important landmark of that era is the Lybico-Punic mausoleum. Archeologists have found that the walls surrounding the city, once thought to be Numidian date to pre-antiquity with a possible construction date of 308 BCE.

The archeological site of Dougga was quiet in the month of November as witnessed by the sheep grazing undisturbed

Dougga’s later monuments attest to its prosperity in the period from the reign of Diocletian (Roman emperor from 284 to 305) to that of Theodosius I,(Roman Emperor from 379 to 395) but it fell into a sort of torpor in the 4th century.

There are few remains of Christianity, suggesting an early decline after the Romans. The Byzantine period saw the area around the forum transformed into a fort; several important buildings were destroyed in order to provide the necessary materials for its construction.

Dougga was never completely abandoned following the Muslim invasions of the area. For a long time, Dougga remained the site of a small village populated by the descendants of the city’s former inhabitants.

The theater is built against a hillside and was completed in 168 or 169 It was funded by Publius Marcius Quadratus. It follows the classic layout of a Roman theater and could hold approximately 3500 spectators.

This sculpture would greet the attendees as they entered. Romans commissioned statues with detachable heads so if a ruler was replaced, or a hero was disgraced, they could swap them out without having to pay for a whole new body as well.

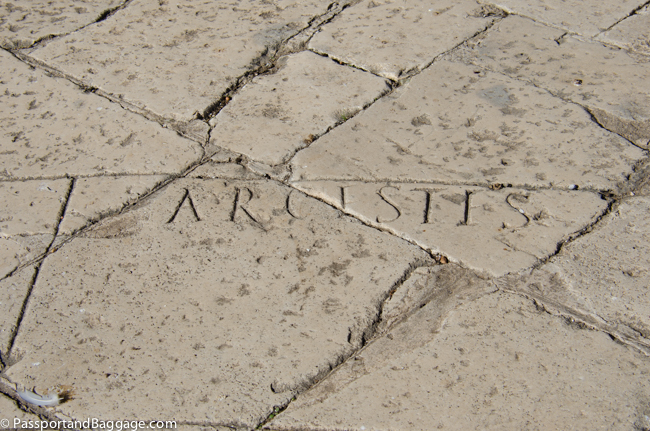

The Temple of Mercury and the Wind Rose Square were built between 180 and 192. The Wind Rose is said to symbolize the role of Mercury as a traveler through the universe and that of the market receiving commodities from the four corners of the world. While difficult to see, it is carved in the marble on the ground and consists of three concentric circles. Two main orthogonal diameters are drawn from the inner circle to the outer circle, and according to the cardinal points, connecting, on the one hand, the North (Septentrio) to the South (Auster) on the other the West (Faonius) to the East (Volturius). The space between the two larger circles is occupied by 24 cantons: 12 of which are filled with the names of the winds.

This large public works project of the Temple and the Wind Rose was paid for by a couple from Dougga. a Quintus Pacuvisu Saturus and his wife Nahania Victoria at a cost of at least 120,000 sesterces.

The Antoninian baths were originally called the Licinian Baths as it was thought they were donated to the city by the Licinian family. A text later found during research showed their construction took place during the reign of Marcus Aurelius Severus Antonius at an undetermined date between 253 and 268. The baths are interesting for having many of its original walls intact, as well as a long tunnel used by the slaves working at the baths. They were primarily used as winter baths. The frigidarium has triple arcades at both ends and large windows with views over the valley beyond.

This is the largest house found in Dougga to date, built around the 3rd century. It was at least two stories tall.

The Cyclops baths owe their name to the mosaic, now in the Bardo museum of Cyclops forging Jupiter’s Thunderbolt in Vulcan’s den.

It is thought this tomb was built around the late 3rd century BCE. It was relatively well preserved until, in 1842, Sir Thomas Read, the then British consul to Tunis removed the inscription commemorating the end of work on the mausoleum. This inscription is now in the British Museum. The monument owes its current appearance to the work of French archaeologist Louis Poinssot, who essentially reconstructed it from pieces that were left lying on the ground.

The inscription was written in two languages: Punic and Lybic. The inscription is incomplete leaving the identity of the person unknown.

The area has so many lovely pieces simply lying around or ruins standing with no explanation. Here are a few of those.

*

After a 20 minute drive from Dugga to find this aqueduct, a dead-end road prevented our continued pursuit. The real distance between the catchment in Dougga and the reservoir where the aqueduct begins is greater than 7 miles.

Ain Tounga

Ain Tounga is a small Roman archeological site with no tourism or signage. It sits alongside the roadway on your way to Dougga

Ain Tounga is often said to have to be finest Byzantine fortress in Tunisia. The fortress was built in the 6th century and has 5 square towers.

Testour

When Muslims and Jews were expelled from Spain in the early 17th century, North Africa was flooded with refugees. Some of the wealthy settled in Tunis, but others who wanted to put down roots nearby had to ask the Ottoman government for land, and they were given the old Roman ruins of Tichilla, now called Testour.

This is one of the few minarets in the world with a clock, but the numbers are placed backward. The story as to why seems to have been lost over time, but most claim it’s because locals wished they could go back in time and return to Andalusia.

The minaret also features the Star of David, a nod to the Jewish community who were also forced to flee Spain and who helped construct the mosque.

Sloughia

The only reason for mentioning this town is our stop for lunch. We began by purchasing the local cheese. It is a simple cheese made from cows milk.

Lunch was some of the most delicious BBQ’d lamb one can have. Sliced in front of you and thrown on the grill.

The traditional Berber bread, tabouna, was warmed on the grill giving it a special smokey flavor. The bread is very subtly flavored with hab hlaoua (aniseed) and named after the traditional clay-domed ovens in which it’s baked.

The two sauces you often find on the table are called harissa. Tunisian cooking revolves around harissa, a fire-red concoction made from crushed dried chili, garlic, salt and caraway seeds. It is served with a pool of olive oil. This is served with bread for dipping. Many say the green is not as hot as the red, this author would disagree. It was the Spanish who introduced hot peppers to Tunisia. The word ‘harissa’ comes from the Arabic, meaning ‘break into pieces’, as the paste is traditionally made by pounding red chillies in a mortar. An old tale says that a man can judge his wife’s affections by the spice in his food – if it’s bland, then the love is dead.

Thus ended a long and wonderful day in the countryside of Tunisia