November 7, 2023

I am here to visit an old friend, James. While he lives in Wales, we have agreed to meet in Coventry so we can gather with other friends in the area.

The town of Coventry was bombed rather heavily during WWII and then suffered from the classic concept of modernization, also known as urban renewal.

And yet, there is much to wonder at, starting with the Coventry Cathedral.

The church was bombed on November 14th, 1940.

The tower, spire, and outer wall of the church survived the bombing, but the rest of this historic building was destroyed. After the war, the cathedral was not rebuilt on site but left in ruins as a testament to the futility of war. The surviving spire of St Michael’s is 245 feet high and is the tallest structure in the city.

Sculpture within the ruins includes:

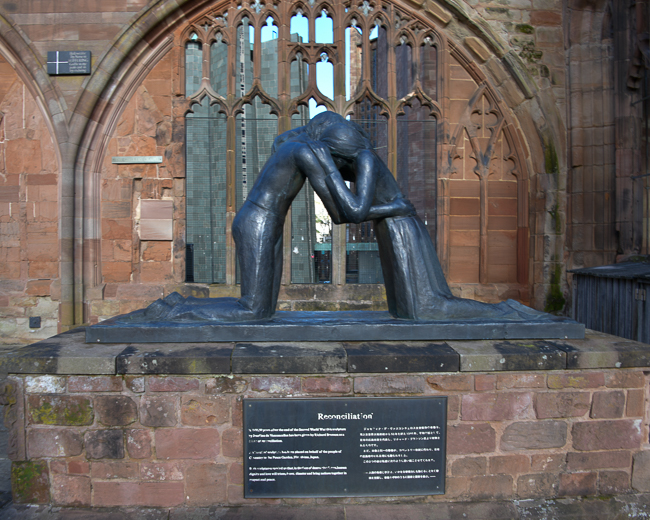

Reconciliation (originally named Reunion) is a sculpture by Josefina de Vasconcellos. “The sculpture was originally conceived in the aftermath of the War. Europe was in shock; people were stunned. I read in a newspaper about a woman who crossed Europe on foot to find her husband, and I was so moved that I made the sculpture. Then I thought that it wasn’t only about the reunion of two people but hopefully a reunion of nations which had been fighting.” In 1995, a copy of the sculpture was placed in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral and Hiroshima Peace Park in Japan to mark the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II.

Bishop Huyshe Wolcott Yeatman-Biggs died in 1922 and was the first Bishop of the revived See of Coventry when St. Michael’s became a cathedral in 1918. His bronze tomb was the only thing within the cathedral to survive the blitz, although one of the bishop’s hands, which holds a small model of the cathedral, was severed. The repaired statue can be found close to where it was originally laid.

The modern building is a stunning piece of architecture that is both an homage to the original and a piece of brutalist architecture that, while standing alone in its beauty, is such a compliment to the bombed-out original Cathedral, designed by architect Basil Spence. It was Basil Spence’s idea to keep the ruins symbolically intact next to the new building.

Both old and new buildings are constructed from the same type of sandstone. The foundation stone of the new cathedral was laid by Queen Elizabeth II in 1956. The interior is notable for its giant tapestry of Christ and the multicolored, abstract design of the Baptistry window that floods the interior with color.

The “Charred Cross” was created in January after the Blitz, when Reverend Howard asked the cathedral’s stone mason, ‘Jock’ Forbes, to make an altar from the rubble and place behind it a cross made from two charred oak beams that had fallen from the roof.

Packwood House

Packwood House is a timber-framed Tudor manor house in Packwood on the Solihull border near Lapworth, Warwickshire.

The house began as a modest timber-framed farmhouse constructed for John Fetherston between 1556 and 1560. In 1904, the house was purchased by Birmingham industrialist Alfred Ash. It was then inherited by Graham Baron Ash (Baron in this case being a name, not a title) in 1925, who spent the following two decades creating a house of Tudor character.

In 1941, Ash donated the house and gardens to the National Trust in memory of his parents but continued to live in the house until 1947.

The Yew Garden contains over 100 trees and was laid out in the mid-17th century by John Fetherston. The clipped yews are supposed to represent “The Sermon on the Mount”. Twelve great yews are known as the “Apostles,” and the four big specimens in the middle are ‘The Evangelists’. A tight spiral path lined with box hedges climbs a hummock named “The Mount”. The single yew that crowns the summit is known as “The Master”. The smaller yew trees are called “The Multitude” and were planted in the 19th century to replace an orchard.

Kenilworth Castle

The first castle on this spot was established in the 1120s by the royal chamberlain Geoffrey de Clinton.

In 1266, Simon de Montfort held Kenilworth against the king in a six-month siege – one of the longest in English medieval history.

In the 14th century, John of Gaunt, son of King Edward III, developed the castle into a palace, building its great hall and lavish apartments.

The castle was a favored residence of the Lancastrian kings in the later Middle Ages. Henry V built a retreat here at the far end of the lake.

In 1563, Elizabeth I granted the castle to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, who transformed Kenilworth into a palace. He famously entertained the queen here for 19 days of festivities in 1575.

The expanse in front, where the Great Dane is romping, is a medieval earthen dam. Built in the 13th century, for 400 years, it held back one of the largest man-made water defenses in Britain, an enormous lake, or mere.

It is possible that during its history, the dam was used as a tiltyard where jousting tournaments took place. King Edward I attended such an event here in 1279 accompanied by 100 knights and their ladies.

The castle’s fortifications were dismantled in 1650 after the English Civil War. Later, the ruins became famous thanks in part to Walter Scott’s 1821 novel Kenilworth, which romanticized the story of Robert Dudley, his wife Amy Robsart, and Elizabeth I.

Walking Around Coventry

The elephant animal appears on the city’s coat of arms and is thought to signify the city’s strength in medieval times.

The Coventry Council House

The Coventry Council House is faced with Runcorn stone and roofed in Cotswold stone. The rich display of heraldic carvings, mostly centered around the main entrance, includes the arms of many historical characters associated with Coventry’s history, from the time of Edward the Confessor until the 16th Century.

The full list, although not all captured in this photograph, includes Edward the Confessor; Henry II; Queen Isabella; Edward III; Edward, the Black Prince; Richard ll; Henry VI; Queen Margaret; Queen Elizabeth l; Mary, Queen of Scots; James l; the Earls of Chester, Cornwall, and Northampton; the Dukes of Norfolk and Hereford; Neville, Earl of Warwick; Sir William Dugdale; Thomas Sharp; John Hales; Sir Thomas White; the Botoners and Swillingtons; Thomas Wheatley; Thomas Bond; William Ford; Dr. Philemon Holland; the Davenports: the Hopkins and Jesson families; Sir Skears Rew; the Harringtons of Coombe Abbey; the Berkeleys of Caludon Castle; the City of London; and the See (bishopric) of Lichfield and Coventry.

Coventry is a college town, and what remains of its history is small but also within a 5-minute walk of the train station and certainly worth a quick jump off the train to explore. The other items in this post definitely require an automobile but are all doable within half of a day.

*

* *

*