December 10, 2019

There are many types of travelers and many types of travel, Tunisia requires a unique traveler for the unique things it has to offer.

There are many types of travelers and many types of travel, Tunisia requires a unique traveler for the unique things it has to offer.

According to Garrett Nagle in his book Advanced Geography, Tunisia’s tourism industry “benefits from its Mediterranean location and its tradition of low-cost package holidays from Western Europe.”

This all came to a roaring halt in 2015 when, in the coastal resort of Sousse, 38 people were killed in a shooting rampage that targeted tourists, while earlier in the year an attack on the National Bardo Museum in Tunis left 22 people dead.

The terror attacks decimated Tunisia’s crucial tourism sector, which made up seven percent of gross domestic product and had already been shaken by the country’s 2011 revolution.

There is a Tunisian faction of Al Qaeda, but most embassies feel travel is safe with a simple warning that travelers should stay away from the borders of Libya and Algeria. One can see the serious measures the Tunisian government is dong to keep people safe when you get on the roads. Approximately every 5th car is pulled over at any random spot, the driver is asked for their papers and then asked to open the trunk. I am not so sure this isn’t like taking your shoes off at TSA, but it makes the citizens feel more secure. As far as this traveler, it never crossed my mind to be concerned.

Fortunately for Tunisia in 2018, Tunisia had around eight million visitors and an increase in the Russian and Chinese market, as well as that of the traditional market, notably the French and Germans.

A very large portion of Tunisian tourism is made up of the above mentioned traditional market that goes to the all-inclusive resorts to appreciate the incredible beaches of Tunisia and know that alcohol is prevalent and easy to get.

Then there is the south around Tataouine, where Star Wars fanatics come on tours to see all of the abandoned movie set locations. You can also do camel treks, four-wheel-drive treks, and mini-safaris. This type of tourism is definitely designed for a specific type of tourist.

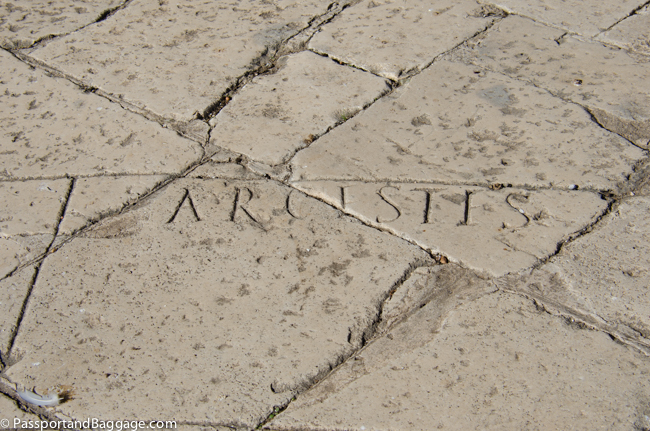

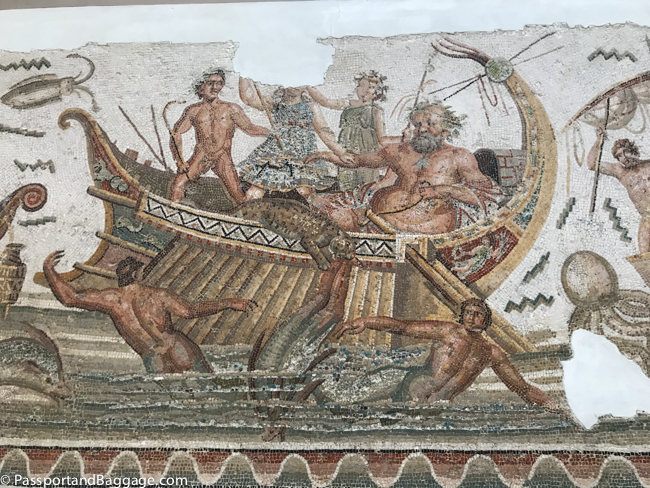

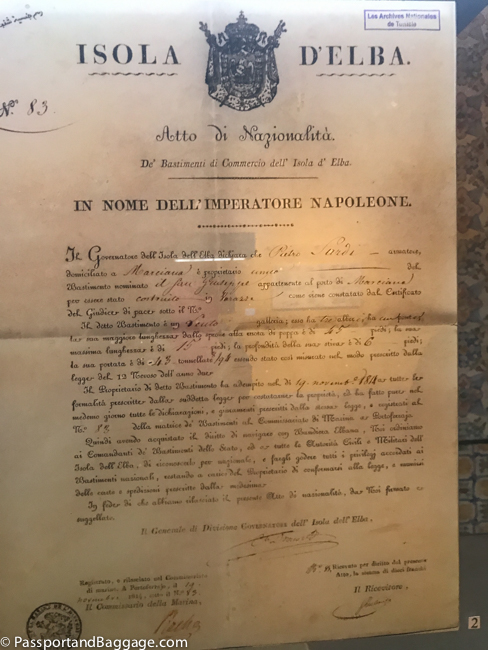

The third reason to visit Tunisia is the complex and incredible history, which is what the last 11 posts have been about.

The third reason to visit Tunisia is the complex and incredible history, which is what the last 11 posts have been about.

This all being said, Tunisia is not quite ready for a tourist that just wants to come to see Tunisia. The hospitality industry is still very untrained and often confused. There are lovely hotels in the larger towns, and I highly recommend staying in a dar, or home, while in the larger cities, however, when you travel to the smaller towns such as Tataouine and Kerouane, the hotels truly lack.

Food is another issue. The food of Tunisia is absolutely delicious, but it is hard to find. Eating off the street or in the small cafes of the medinas will guarantee you get a wonderful meal, in the average hotel, not so much. There are excellent meals to be had in the 5-star hotels, and still at a very good price, but those do not exist in the smaller towns. The good food of Tunisia is cooked at home.

Food is another issue. The food of Tunisia is absolutely delicious, but it is hard to find. Eating off the street or in the small cafes of the medinas will guarantee you get a wonderful meal, in the average hotel, not so much. There are excellent meals to be had in the 5-star hotels, and still at a very good price, but those do not exist in the smaller towns. The good food of Tunisia is cooked at home.

Getting around can also be problematic. The one thing you should know before you ever set out is to never trust Google maps estimated times. They are simply wrong. We rented a car and found the roads to be excellent but our driving time was far longer than estimated by Google. There is the new A-1 which was still under construction throughout most of Tunisia, but when it comes online it will speed up travel times considerably. The A-1 is part of an international project, called either the Trans-Maghreb, Trans-North Africa Highway or Trans-African Highway 1 planned to eventually reach from Cairo to Dakar.

In many towns, there are taxis you hail like anywhere in the world. There are little vans that are shared taxis if you can decipher their routes. There are trains, and airports spread throughout Tunisia, making travel easy if you are willing to make the effort.

French and Arabic are the two most spoken languages of Tunisia, finding an English speaker is actually quite rare. My second language is Spanish with Italian in a pinch, but they were completely worthless. Like any country in the world, language is not a barrier if you have a smile and some time, but in an underdeveloped country like Tunisia, you may find some of the simpler things, like asking about an illegible hotel or dinner bill, to be difficult at best.

Here are some of the places we ate and stayed with my personal comments. I am an adventurous traveler, but I am also a fan of good food, good service, and clean rooms. One other note, the “we” is two women of indeterminant age, which is important when you consider we did a lot of driving.

Tunis – 5 days

Sadly this was actually one day too short, thanks to the driving situation as mentioned above

El Patio Courtyard House. A sweet home in the Medina where the family still lives. The breakfast was wonderful, the rooms decorated perfectly and the amenities were all there. They were very helpful in helping to arrange drivers to some of the distant places we wanted to go. They still have a ways to go regarding the quality of bedding and the amenities, but their kindness makes up for it.

The amenities in many of these places are one of the things to consider. If you are particular about soaps and shampoos, bring your own. In several places, a small bar of soap was all that was available in the rooms. In most others the color and fragrance of the bath items were more akin to what one would find in the cleaning supply aisle as opposed to the beauty aisle.

Restaurants I recommend: Dar el Jeld, which is also a five-star hotel inside the Medina

The restaurant in the Hotel Palais Bayram in the Medina

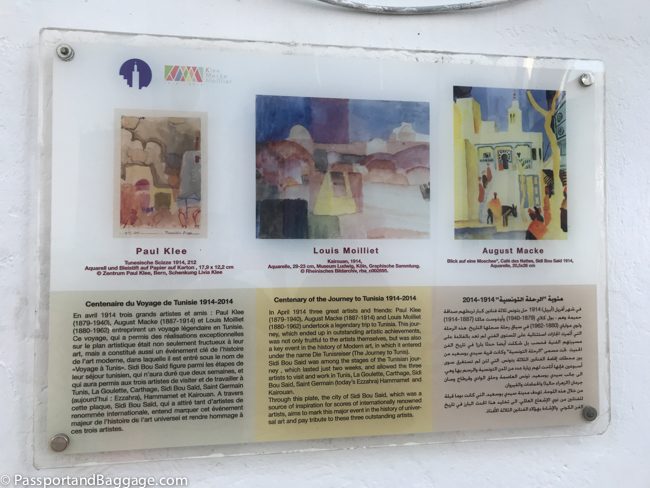

The restaurant in the Hotel La Villa Bleue in Sidi Bou Said

Day 1: Getting one’s feet on the ground by wandering the Medina of Tunis and the French area called New Town

Day 2: A cab to Carthage for a full day of exploring and dinner at Sidi Bou Said

Day 3: The Bardo

Day 4: Dugga. The plan was a day trip to both Dugga and Bella Reggia, due to the roads, we were unable to do them both on the same day, which sadly means, I never did see Bella Reggia.

Day 5: A day trip to Kerkouane

Then in the early morning a flight to Djerba and pick up a rental car to drive to Tataouine.

Tataouine

There are not many hotels in this area, and I can not recommend a one. They are set out as resorts, with swimming pools and will meet the needs of a backpacker or severely economic traveler, but not many others. The food in the hotels was so bad that simply mentioning it gives it more credit than is due.

Day 1 – Stop at El Jem on the way down to Tataouine.

Day 1 – Drive to various Berber villages admiring the architecture and the Ksars.

Day 2 – Drive to the town of Chenini with a stop at Dourite.

Sfax

Sfax

The Business Hotel Sfax. A perfect spot after the rooms and food at Tataouine. There is a dining room with 365-degree views, but it was under renovation, so dining was in the bar with the same menu. No complaints, I had the Ojja Merguez and it was great.

This was just a halfway point stop so we really did not do anything but roll into town, sleep and roll out again.

Kairouan

Day 1 and 2: Explore the sites of Kairouan. The hotel was the Hotel Continental. With the exception of a lovely front desk staff, I can not say one good word about this hotel or its food.

Sousse

We dropped the car off at the Monastir airport and got a ride into Sousse from the rental car guy. That is a comment on the amazing kindness of Tunisians, they go out of their way to do little favors for anyone and everyone.

Dar Antonia for lodgings: The very best of the entire trip, perfect in every way. The staff is so very kind, the rooms are perfect ad the breakfast, hearty, healthy and delicious. This was the first place we stayed with palatable coffee, an FYI for people that can not rise without it.

Most likely because of the Europeans that once frequented this area and its all-inclusive beach hotels, this town is far more sophisticated and understands good food and good service.

There are several good dining spots in Sousse:

El Kasbah, both for a great lunch or a hangout with Coffee Turk

Restaurant Dar Solton – is heavy Tunisian food, so go with an appetite. They serve wine

Restaurant La Caleche – fabulous fresh fish – they serve wine.

For lunch – Restaurant Sofra. You walk in sit down and then they will come tell you what has been thrown on the grill for the day – or coming out of the kitchen. Perfectly grilled fish and a side dish made with broad beans, and greens that was just fabulous. Their bread was the freshest I tasted.

Bread is a HUGE part of the Tunisian meal. So the fact that so often the bread served was not fresh was always astounding to me. Big hotels go through hundreds of baguettes a day, and yet, they always seemed stale.

The griller at Sofra restaurant in Sousse. He does not speak a word of English, but he has the nicest smile and the kindest way about him.

Food

As I have mentioned, the best food in Tunisia is eaten on the streets or the small cafes in the Medinas. When you find a five-star hotel, you will find good food, and there you will also find wine. The following items were some of my favorites.

Lamb at a roadside stop where they cut the lamb from a carcass and grill it on the spot. To me, this was the perfect meal.

This was from the restaurant Safra in the Medina at Sousse. The fish was just off the grill that you see in the photo above.

This type of bread is Mlawi. You order it stuffed with what you want. In this case, it was lamb, but you will find them stuffed with tuna, cheese and any other combination of things. While this one was in a cafe, there are hundreds of street stalls that sell them to you so you can walk away with them.

This is a brik. Pronounced breek. They are filled with a variety of things, but the egg is the most common. It is vital it is still runny when it arrives in your hands

Coffee and mint tea are easy to find in Tunisia. The Coffee Turk always comes to the table in a beautiful cup

Citronnade of Tunisia is a highly concentrated lemon juice mixed with either simple syrup or powdered sugar.

I have discussed here, that Tunisians do have a wine industry. They also have one beer. It is a pilsner type beer and comes in at 5%.

One little tiny note about leaving Tunisia. It is illegal for the Tunisian Dinar to leave Tunisia. No, they are not going to arrest you, they are simply worthless once you leave the country. No other country will trade their currency for the TD. The thought by this author was to use the last thirty-some dollars I had in TD for some last-minute shopping before boarding the plane. Alas, in Tunisia, once you cross security you are in no-mans land and all the stores and cafes in the post-security area will only take Euros, so I have a lot of worthless paper in my wallet right now.

*

*

*

*

*

*