December 2022

Hill House

When I was here just two months ago, I concentrated on the architecture of Alexander Thomson as I had too little time to discover the works of Glasgow’s most famous architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh. At the time, I knew I was coming back for three days of a whirlwind through Mackintosh. What I did not count on was the fact that the daylight only lasts until 3:30 and that it would be 18 degrees outside. More importantly, many of Mackintosh’s works are outside of town, so visiting isn’t as easy as one might imagine. All that being said, I put a pretty good dent in the quest.

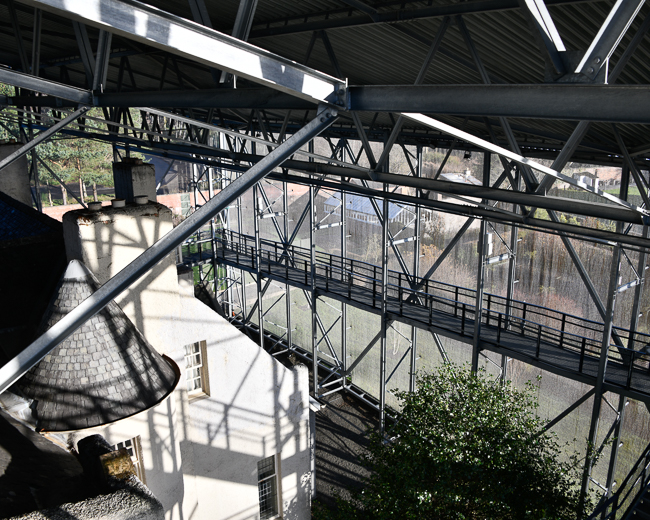

Mackintosh used the most modern material for the exterior of Hill House, concrete. Sadly, the technology wasn’t yet sufficient to understand that Lime was imperative to the mix. For this reason, Hill House had become so damp as to be a mere two years away from complete ruin. To protect the Hill House, the National Trust of Scotland constructed the Hill House Box, a protective steel frame structure covered in a chainmail mesh designed to protect the house from the harsh Scotland weather, allowing the walls to dry and prevent further damage.

I had read all about this in a historic preservation magazine and then promptly forgot about it; it was a thrill actually to come upon it and see it in situ.

Living Room of the Hill House. The wingback was not a Mackintosh design; it was the chair Mrs. Blackie liked to sit in at the fireplace. Over the fireplace is Margaret’s The Sleeping Princess, commissioned by Mrs. Blackie in 1908, four years after the house was completed.

The Hill House is considered to be Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s domestic masterpiece; it was commissioned by Glasgow book publisher Walter Blackie.

Although Mackintosh always gave his wife, Margaret Macdonald, credit, it doesn’t seem that the public does, even to this day.

Remember, you are half if not three-quarters in all my architectural work ….”

“Margaret has genius, I have only talent.”

– Charles Rennie Mackintosh on Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

Queens Cross Church

Queen’s Cross is the only church in the world designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh and then constructed. Commissioned in 1896 by the Free Church, its draw is its absolute simplicity.

The Willow Tea Room

Mackintosh and Macdonald were kept very busy designing and creating tea houses for Ms. Kate Cranston, a brilliant businesswoman, a lover of the Mackintoshs’ work, and patron extraordinaire.

Two of the tea houses were completely restored by the Willow Tea Room Trust in the early 2000s, and profits go to the continued restoration and maintenance of the Tea Rooms.

The Room Deluxe served the creme de la creme of society. It included aluminum-dust-finished chairs, a glass chandelier, and a gesso work by Margaret that now stands in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

Plaster sculpted walls of the Front Saloon (the twinkle lights are not normally there, it is Christmas time)

The Lighthouse

The Lighthouse is Scotland’s Centre for Design and Architecture. The building formerly housed The Glasgow Herald, and was the first public commission completed by Mackintosh. Sadly it was still closed “due to covid” while I was there.

The ornamentation on the exterior of the lighthouse demonstrates the light touch of Mackintosh towards such displays.

The Mackintosh Home at The Hunterian

The Hunterian has reassembled the original interiors from the home the Mackintoshes rented, designed, and lived in from 1906 to 1914.

Once the re-assemblaged was accomplished, the home was furnished with the Mackintoshes’ own furniture.

The chairs in the dining room were Mackintosh’s first ‘high-back’ and were based on a design for Miss Cranston’s Tea Rooms.

The Studio Drawing Room was originally two rooms, altered by the Mackintoshes. The stenciled chairs and oval table were part of an ensemble called ‘The Rose Boudoir’ exhibited in Turin in 1902.

I found the black and blue in the guest room to be especially interesting.

The Hunterian is part of the University of Glasgow, which, thanks to a donation by the Mackintosh’s nephew, has a large collection of Mackintosh’s drawings, designs, and watercolors, along with over 40 works by Margaret.

Mackintosh was not highly appreciated in his own lifetime and has really only been brought to the for of architectural fame in the 21st century. Fortunately, his works have survived and now hold a place of pride in Glasgow.