May 2024

In 1788, Maryland ratified the the U.S. Constitution. On that day, 4,000 Baltimoreans gathered to celebrate, and the celebration concluded on the hill, giving it its name. In 1797, an observatory was opened at the hill’s peak, enabling merchants to receive advance word of ships approaching the harbor. During the War of 1812, Federal Hill served as an observation post and signal station. When the British bombarded Fort McHenry, many citizens watched from the hill.

View from Federal Hill

Early in the colonial period, the area known as Federal Hill was the site of a paint pigment mining operation. The hill has several tunnels beneath its park-like setting that occasionally collapse, requiring infill.

View of the Inner Harbor from Federal Hill

On the night of May 12, following the Baltimore riot of 1861, the hill was occupied in the middle of the night by a thousand Union troops and a battery under the command of General Benjamin F. Butler. During the night, Butler and his men erected a small fort with cannon pointing towards the central business district. Their goal was to guarantee the allegiance of the city and the state of Maryland to the United States government. This fort and the Union army presence persisted for the duration of the Civil War.

The top of Federal Hill

The Federal Hill neighborhood, situated on the south side of the Inner Harbor, was the home of shipyards from the late 18th century and the home of the related business owners and workers.

Row houses of Federal Hill

Most houses in the historic district of Federal Hill date from the mid-to-late-19th century, although a smattering of earlier structures also exists. These were primarily the homes of sailors and shipyard workers who worked at the port. All are of brick construction with extensive use of white marble trim, and most are attached row houses of two or three stories in height and approximately 15 feet in width.

White marble stairways of Federal Hill

A 1/2 row house on the right

With only a single room per floor, half-houses were generally built as rentals for those at the lowest income level. The house above is part of a historically African American section known as the Sharp-Leadenhall neighborhood, established in the 1790s by freed slaves and German immigrants. These row houses were sold to freed craftsmen, including carpenters and blacksmiths.

One of the last wood houses in Baltimore

In February 1904, a two-day fire utterly destroyed downtown Baltimore. H.L. Mencken said at the time, “The burned area looked like Pompeii.” The fire obliterated 86 city blocks, consumed 1,526 buildings, and destroyed 2,500 businesses. The fire was the end of wood houses in Baltimore, although a few still stand.

An old firehouse converted into a home.

The United States did not have government-run fire departments until around the time of the American Civil War. Prior to this time, private fire brigades competed with one another to be the first to respond to a fire because insurance companies paid brigades to save buildings. This was the home of the Watchman Volunteer Fire Company. The building was constructed in 1840 and decommissioned from fire service in 1859 when Baltimore City took over all-volunteer fire companies and converted them into paid fire companies. It is the oldest standing firehouse in the City of Baltimore and possibly the oldest standing firehouse in Maryland.

A home on Federal Hill I found unique due to its curved front.

American Visionary Art Museum of Baltimore

At the foot of Federal Hill is one of the most unique art museums I have had the privilege to visit. The museum specializes in the preservation and display of outsider art (also known as “intuitive art,” “raw art,” or “art brut”).

The founder and director of the AVAM is Rebecca Alban Hoffberger, who, while working in the development department of Sinai Hospital’s (Baltimore) People Encouraging People (a program geared toward aiding psychiatric patients in their return to the community). Hoffberger became interested in the artwork created by the patients in the People Encouraging People program and found herself “impressed with their imagination” and looking to “their strengths, not their illnesses.”

The founder and director of the AVAM is Rebecca Alban Hoffberger, who, while working in the development department of Sinai Hospital’s (Baltimore) People Encouraging People (a program geared toward aiding psychiatric patients in their return to the community). Hoffberger became interested in the artwork created by the patients in the People Encouraging People program and found herself “impressed with their imagination” and looking to “their strengths, not their illnesses.”

The entryway floor is made of toothbrushes.

Outsider art is made by self-taught individuals who are untrained and untutored in the traditional arts and typically have little or no contact with the conventions of the art world. Wandering the museum, I became enthralled with the story of the artists’ lives, almost more than their art.

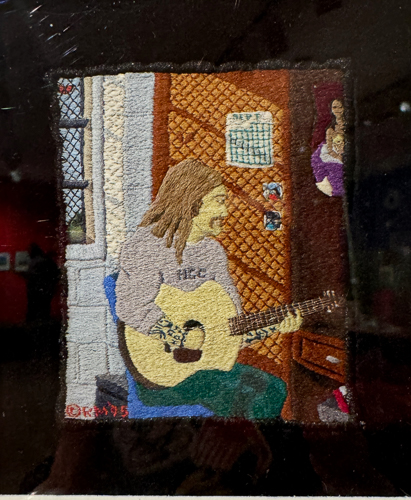

The Art of Ray Masterson

One that really sticks with you is Ray Masterson. Born March 15, 1954, in Milford, Connecticut, Raymond Materson grew up in the Midwest. He earned a G.E.D. and attended Thomas Jefferson College as a drama and philosophy major but was plagued by a serious drug problem. To support his habit, he committed a string of robberies with a shoplifted toy gun, was eventually arrested, and sentenced to 15 years in a state penitentiary in Connecticut. To keep himself sane, Ray taught himself to embroider, using unraveled socks for thread and a sewing needle secured from a prison guard. He stitched miniature tapestries depicting life outside prison walls and sold his works to other inmates for cigarettes. Most of Materson’s miniature embroideries include approximately 1,200 stitches per square inch, measuring less than 2.5 x 3 inches.

One of my favorites: World’s First Family of Robots by DeVon Smith