October 2021

Casa Vicens

Casa Vicens was designed as a summer home, so looking at the airflow, windows, and screens is a part of understanding the design. In 1883, Manel Vicens i Montaner, a stock and currency broker hired Gaudi to design this summer garden home in what was, at the time, the former village of Gràcia. This is considered Gaudi’s first masterpiece.

Vicens died in the house in 1895. Over the years it was enlarged and divided into four apartments. In 2014, MoraBanc, a private bank bought the property and restored it to its present state and converted it into a museum and exhibition space.

Only a few rooms are restored to their original, from there, they did a wonderful job of creating what the space would have looked like, but painted all of the surfaces white to differentiate the new from the original.

The house now sits in a very developed area with extremely narrow streets, so getting an overall photo of the house is difficult to say the least.

Most museums now find it convenient to point you to a downloadable audio, or even hand you a headset with all the information available. In all of the Gaudi homes, there is a QR code and you can download the audio guide to your phone. This means everyone is walking around with their phone to their ear (sans ear buds), or at full volume so the whole family can hear, making it impossible to actually concentrate, especially when there are six different languages occurring. I skipped the opportunity in every case, and spoke to the docents instead. My experience was far richer for it.

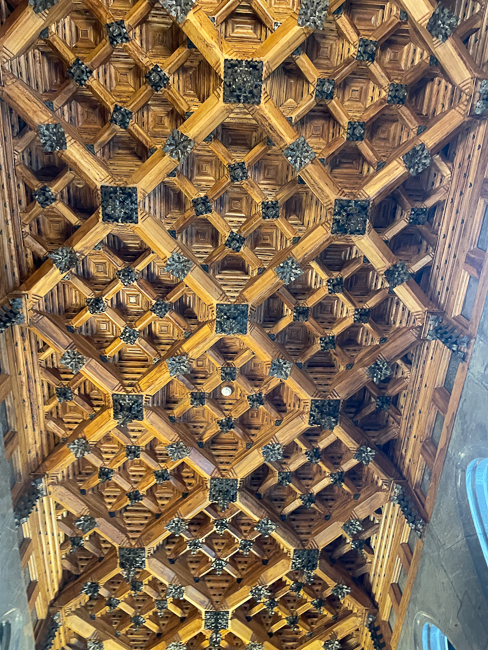

This is the first room you enter in Casa Vicens. My mouth dropped to the floor, I gasped and couldn’t move from my spot. Fortunately a divine docent, fluent in five languages, was there to get me moving again. The first question I asked was about the craftspeople of the house. Gaudi was an amazing architect, and often did not work with drawings but concepts that he was specific about, but left to craftspeople to articulate.

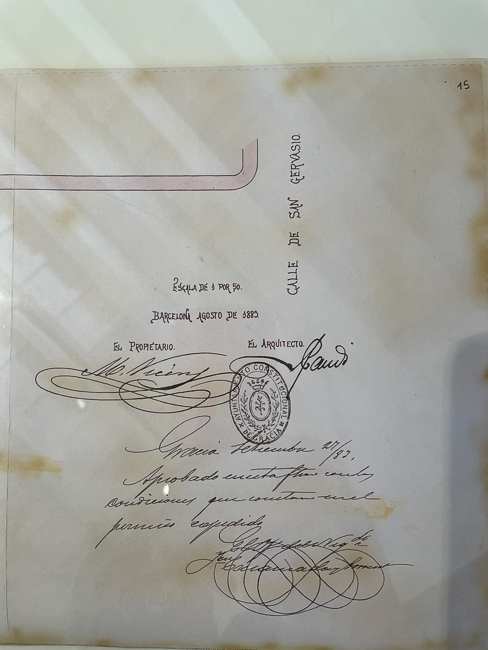

The sad thing is that during the Catalan revolution Gaudi’s drawings and notes were completely destroyed, so in most Gaudi sites my questions about the craftspeople go unanswered. Fortunately the drawings and information for Casa Vicens, were in the house itself, and so there is actually information about the craftspeople.

What you are looking at is a form of papier-mâché created by Hermenegild Miralles. Together with Ramon de Montaner i Vila, he founded a large lithography and industrial binding company, introducing this form of what they called, imitation papier-mâché.

From here I am simply going to share with you the things that brought tears to my eyes for their beauty. Understanding the rooms in Casa Vicens is not important, the craftsmanship it.

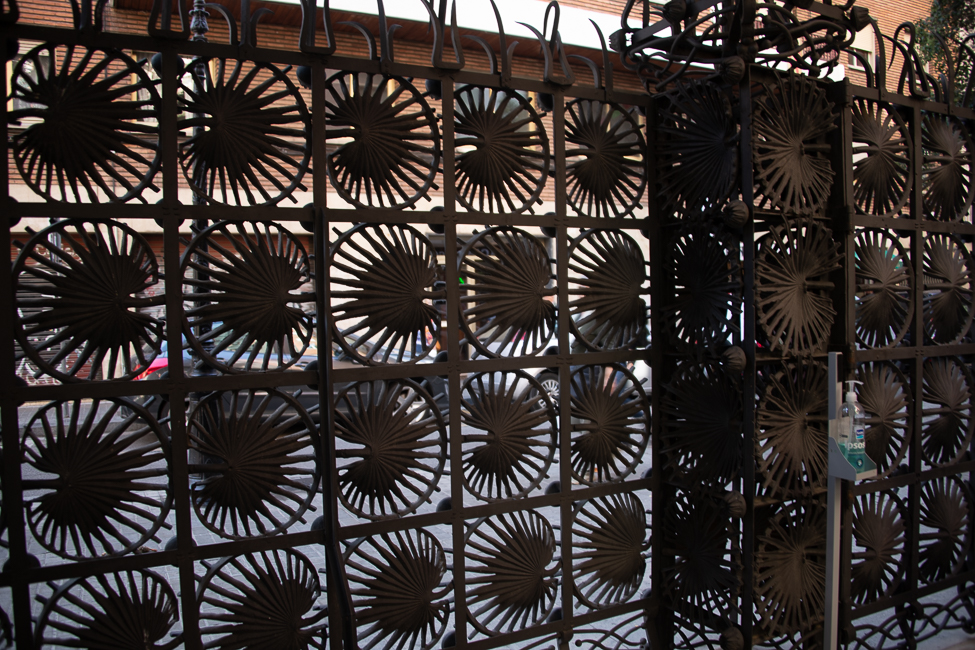

The exterior patio. Notice the screens that allow air to flow catching whatever breezes there were to cool the house in the summer.

I was especially charmed by the front entry wrought iron fence.

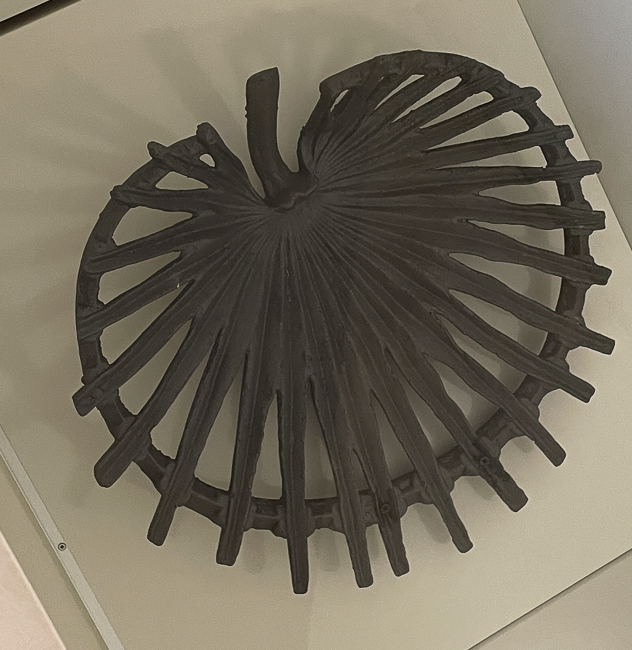

The docent pointed out that Gaudi saw a palm leaf, thought it would make a perfect gate so had the artist, Joan Oñós, make a mold. Since that is actually something that still occurs today, I enjoyed the step through time.

Paseo de Gracia

Photographing street tiles, unless freshly laid, is not easy. It is hard to find where the world has not added such detritus as to make them rather unappealing. These were designed by Gaudi.

Photographing street tiles, unless freshly laid, is not easy. It is hard to find where the world has not added such detritus as to make them rather unappealing. These were designed by Gaudi.

The tiles were originally meant for Casa Botilló, but they were not completed in time, they were then put into Casa Mila. The pattern is hexagonal with three different shapes inspired by three marine elements: a starfish, algae of the genus sargassum and a snail fossil of the Ammonite class; the complete drawing can only be seen with seven tiles. It is monochromatic; the lack of color is replaced by the relief, which provides lights and shadows.

In 1997 the city of Barcelona paved the broad pedestrian zones along Paseo de Gracia with a re-edition adapted to outdoor spaces as a tribute to Gaudi.

Portal Miralles

In 1901 Industrialist Hermenegild Miralles purchased a plot of land in the Sarriá neighborhood of Barcelona, to build a new home. He hired Gaudí to design and build the perimeter wall. The house is long gone, but the entry gate remains.

The three-dimensional cross at the top of the arch is one of Gaudi’s trademark motifs and can be seen decorating several of his buildings.

The gate was last restored in 2000 and at that time a life-sized bronze statue of Gaudí by Joaquim Camps was added.

Street Lights

While in school, Gaudí worked with Josep Fontserè i Mestre as a draughtsman for the entrance gate to the Ciutadella Park. Upon finishing this project, the Barcelona City Council commissioned him to design the public lighting of two of the city’s squares: Placa Reial and Pla de Palau. These 6 arm lamps are in Placa Reial.

The lampposts show the Barcelona coat of arms in the middle of the column. On the top of the lampposts in the Placa Reial is Caduceus with two snakes and a winged helmet, symbolizing Mercury, the Roman god of commerce.

In Pla de Palau the same Gaudi street lights can be found but with three arms that are not as ornately decorated. At the top of these lampposts is an inverted crown, supported by three dragons.

Palau Güell

Palau Güell was one of Gaudi’s first works, and was for his patron Eusebi Güell. Construction began on the house in 1886 with the opening during the 1888 World Exhibition. Originally to be a multipurpose building with apartments, and event spaces it was not easy to place all of that into the small footprint of the lot.

Everything you read about this structure waxes poetic about its brilliance. I found it almost macabre. I can not, again, rave enough about the quality of the craftsmen, but I kept looking for the chained up fire breathing dragon in the basement.

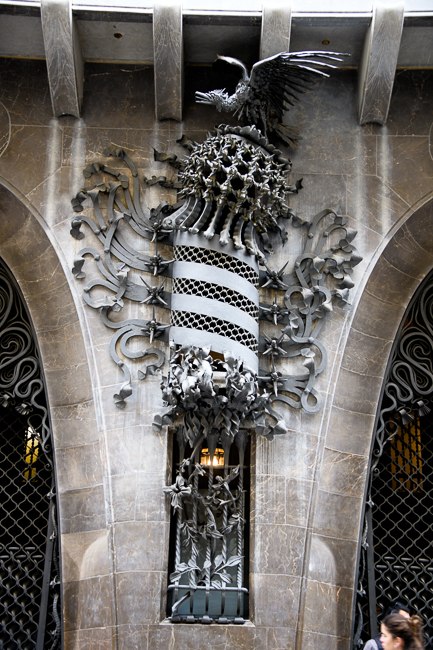

The foremost feature on the front of the house is this wonderful sculpture of ironwork. The exterior of the house is all limestone from nearby Garraf

This entry hall is crowned by a parabolic dome, which lights the whole space through a series of small openings and a large central oculus. The entire building is configured around this central hall. The purpose of much of this room was not just to wow you with its aesthetics, the design guaranteed impressive acoustics for the concerts and religious services held here so they could be heard throughout the home.

Like so much of Gaudi’s work, you don’t need to really understand the purpose of the rooms as to simply ogle at the craftsmanship.

When I was visiting Casa Vicenza there was a collection of Gaudi’s personal books, my eyes fell upon a pattern book filled with Islamic tiles, I saw much of that throughout several of his works, but here it was truly obvious.

The back façade of the house is viewable from an exterior terrace: the lower part of this interesting structure is covered with blue-tinted azulejos (tin-glazed ceramic tiles) while the upper part has a balcony and a wooden pergola.

If there was a chained up dragon in the basement I never found him, but I did find Gaudi’s whimsey on the roof.

I do not want to give the impression that I did not think this house was anything other than spectacular. It is simply that so much of Gaudi’s work has a lightness to it, you can feel his smiling, his quick step, his bright and brilliant mind, here, the spark was replaced with a darkness I simply did not expect.