December 2019

Morocco has six Medina’s on the World Heritage List, and I started to wonder why. Was it to protect them from Urban Renewal, or was it something else? This brought up a question for me which no matter how many people I asked, or articles I read, I still did not really get an answer. That question is how do you bring the Medina forward to function in a more modern world, and not lose exactly what makes the Medina the Medina.

I must note here that as I started to do a deep dive into this question I realized that it had been brought up by UNESCO, The World Bank, The Moroccon government and thousands of charitable organizations, and as of yet, there are no solid answers. The concentration of these organizations has been in Fez, so much of this conversation will be focused on that Medina. However, I still have questions as to why all six? They each are important to their own town, and yes they are a part of not only the history of each town, but also of the ancient history of Morocco itself, and individual buildings within them are often important, but the spaces themselves are all very much alike from town to town. While I believe the point of making all six a world heritage site is an attempt to hold onto a culture, I question whose culture?

Also, this is simply a personal exploration, I have no answers, just questions.

The walls of the Fez Medina stretch for over 8 miles, some are in poor shape.

In its sphere of cultural programs, UNESCO’s stated role is to act as a champion of diversity against globalization and to protect distinct cultural identities. This is a noble concept but it hides so many issues regarding the act of actually preserving the Medinas, versus the way of life of the people that actually inhabit it.

Placing Medina’s on the World Heritage List ensures that they will not be torn down or altered too drastically, preserving the architecture, but does it preserve anything else?

Countries from all over the world are coming together to help Fez recreate or restore many parts of the Medina, and a few have proposed some radical changes as well. One can easily argue that this is progress, and it has happened and is happening across history and across the world, but as the world population grows and the disparity between have and have nots increases exponentially, isn’t it time to also look at how these improvements are uprooting the poor and their way of life. This can be easily countered with, these improvements are for the greater good.

Part of this progress is the wealthy coming into the Medina’s buying up rundown Riads or Dars ( riads have a garden (the Arabic word riad means garden), and dars have a courtyard) and turning them into tourist hotels. This is bringing jobs. There are now construction jobs as buildings are being either restored or replaced. As the Riads and Dars, become hotels they will employ staff to cater to the tourists. This is the upside of this new movement. The downside is the fact that the middle class, exactly who the government wants to move back into the Medina’s, have already been priced out of the market, as it has been primarily the wealthy that have purchased these properties.

How does Tourism play into this?

Moroccan Tourism Observatory has reported that more than five million tourists visited Morocco in the first half of 2019. The number represents a 6.6 % increase compared to the same period last year, and that tourism is considered as one of the main foreign exchange sources.

With the development of tourism, Medinas became a destination for foreign tourists. This very development, however, caused a collapse in some crafts in favor of trade. It became very difficult to maintain the traditional activities and crafts of the souks within the Medina, all because adapting to the needs and expectations of tourists had become a priority.

This street is just as you enter the Fez Medina from the Blue Gate. It is called Rainbow Street and is listed in every Chinese guide book as the place to shop

This increase in tourism to purchase trinkets made in China has also lead to the proliferation of hucksters and con-men that are making visiting the Medina’s less and less enjoyable. A simple google search of articles regarding being scammed in Morocco will bring up a million results. This is not good for the industry, I have watched women leave the Medina out of fear, and the stress level of the overwhelming amount of men approaching you to be your “guide” makes one question the desire to even enter into these historic spaces with the treasures they have to offer.

The Government of Morocco proposed a project to boost artisanal household incomes once they discovered that tourist spending on local artisan products was substantially lower than in comparable foreign markets. This was due in part to the fact that many artisans lacked the training and skills necessary to modernize production and capitalize on this growth. The Artisan and Fez Medina Project was designed to stimulate the growth of these arts and tie them back to the culture of the Medina. However, China has flooded the market with look-a-likes at far cheaper prices, and going home with an original Moroccon craft can be hard to guarantee to a less-knowledgeable buyer.

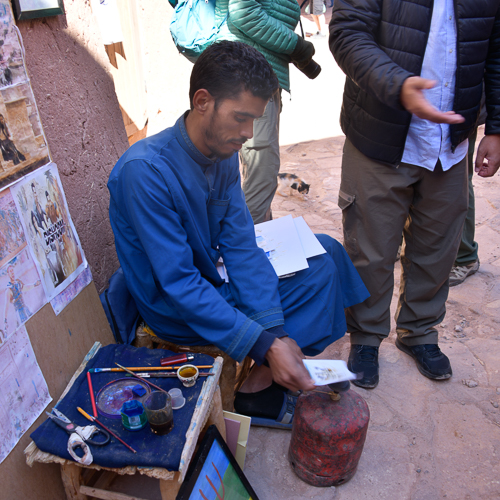

Part of this program, oddly enough, was to move the pottery industry out of the Medina due to its polluting effects. The potters burned the remains of the olive oil production process, olive cake, to fire the kilns, creating a dark sooty smoke. Eventually, this type of kiln was completely outlawed and kilns are now natural gas, expensive, as Morocco has no natural source of Natural Gas, but far cleaner.

One of the outlawed kilns once used in the pottery business

The olive cake is one of the by-products that is generated when processing olive oil. The physical composition of the olive cake is skin, pulp, the stonewall, and the kernel.

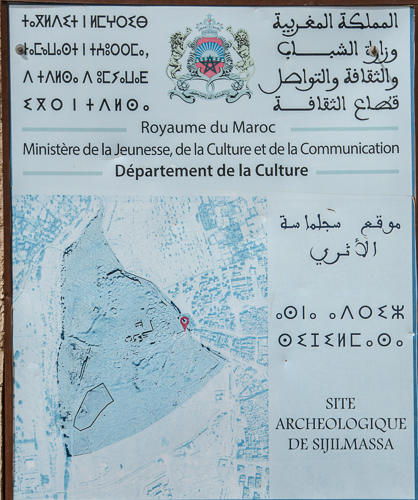

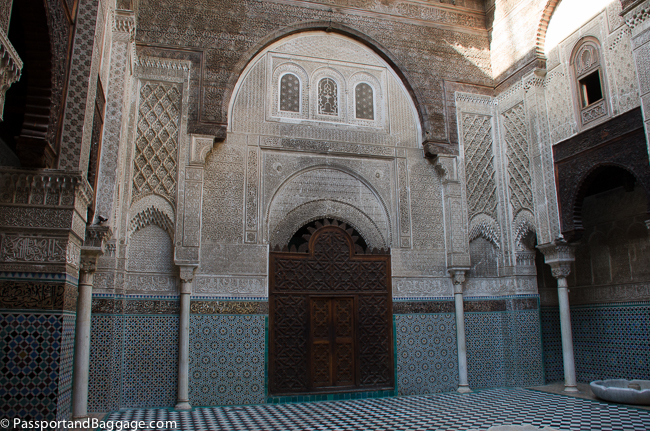

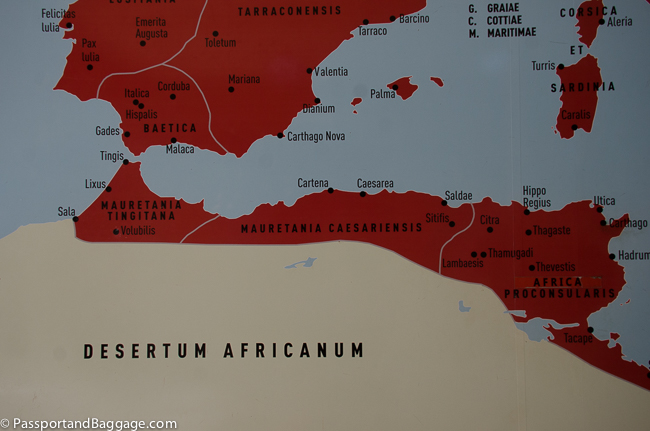

The Fez Medina was founded in 808 and is the largest pedestrianized Medina in the world. It was placed under World Heritage Protection in 1981, and in 1989 the Moroccan government created ADER Fès (Agency of Development and Restoration) to allocate funds and devise projects for the conservation of both the Medina and its culture.

According to Fouad Serrhini, Director General of ADER Fès, “The most important challenge for us is safeguarding the Medina itself – its rehabilitation and the improvement of living conditions for the inhabitants, tradesmen and craftspeople who work there,” “And beyond that to ensure it remains a jewel of cultural tourism.”

Iraqi architect Alaa Said who runs architectural tours of the Medina has said “Preserving the Fez Medina is a very particular challenge because we can’t just turn the whole city into a museum,” “Too strong a dose of modern development could destroy the fantastic character of the city. It’s been key that planners and national authorities find a good balance between conservation and development and provide a framework where the Medina remains a viable, living city equipped with necessary services and amenities.”

Therein lies the largest problem as I see it.

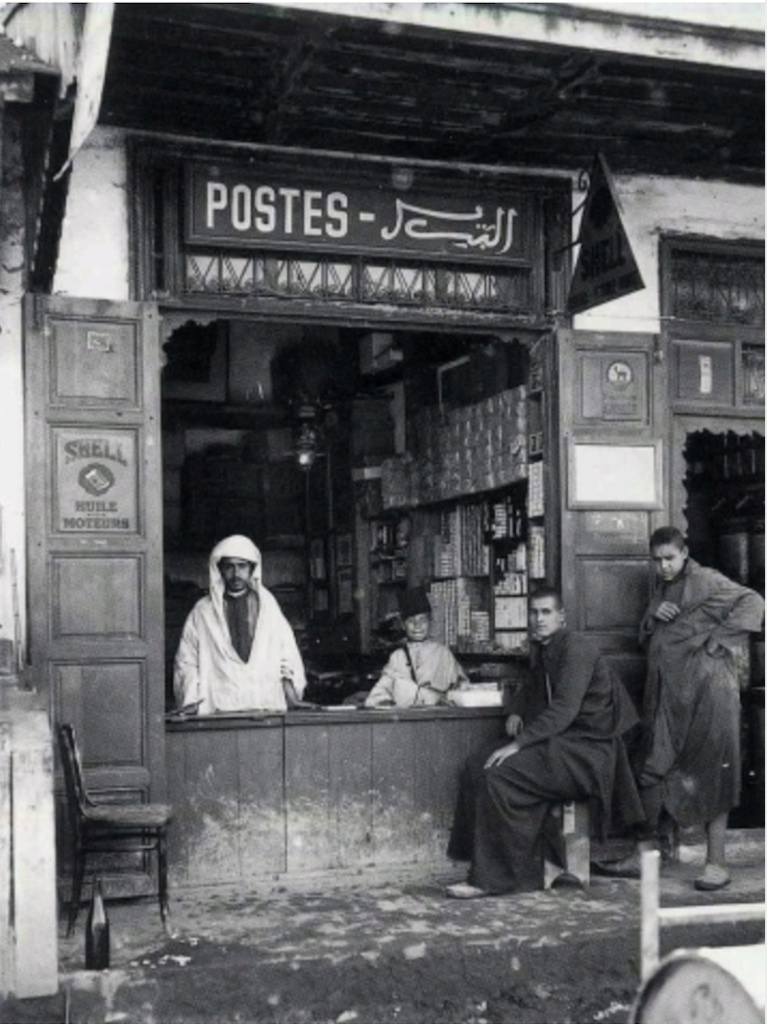

Mail Delivery and Bread Baking

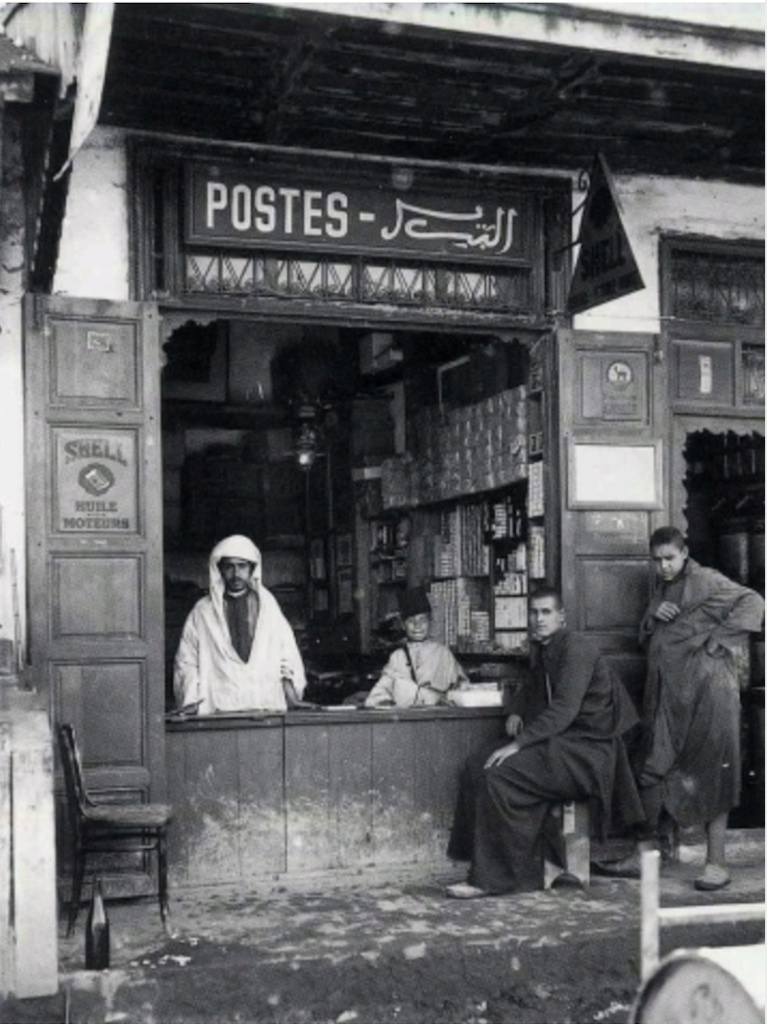

There are officially eight neighborhoods in the Fez Medina. They each still have their own central bread baker and their own mosque. Mail was often delivered to the baker and when he saw the recipient he would give that person his mail. In time each neighborhood was given its own post office. Today the mail is centralized as in most world cities.

Bread is still traditionally made by women in the home and then taken to the central baker to be baked. This once was also true with Tajine. The purpose of this is to keep the possibility of fire down. Today most homes cook with propane, but bread is still baked the old fashioned way. Hopefully, that will never go the way of the post office.

Upgrading the Water System.

Part of the River Remediation and Urban Development Scheme has uncovered parts of the Fez River that runs through the Medina.

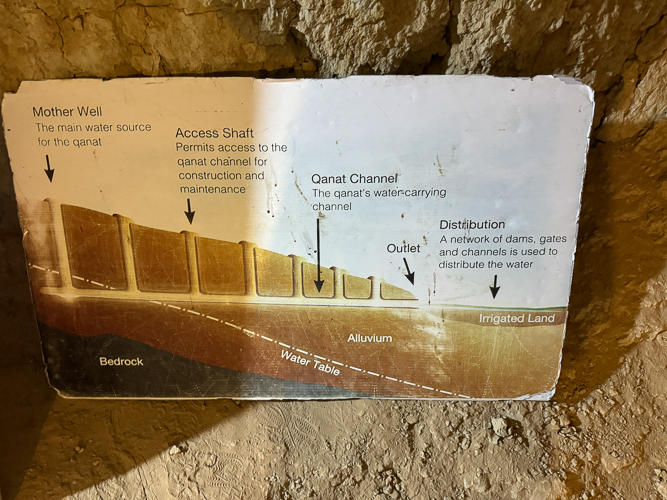

The upgrade of the Medina’s water system is one thing everyone can agree on is a priority. The water of Fez is scarce and of low quality. The Medina sits in a gap between the Saiss plain and the Sebou valley. This gap is the only way for water to go down from the Atlas Mountains.

The presence of water in street fountains, houses, and religious buildings are a result of a system built by the Marinid Dynasty over 800 years ago utilizing the then abundant water. The medina was designed with three kinds of water circuits, water from the river for domestic tasks, spring water to drink and a sewage system. Each house was connected to these three circuits. This all worked on a natural hydraulic system of water flowing from high to low, with rats doing their part in keeping the system clean. Over time roads replaced the water channels and homes replaced the gardens that were inside the Medina causing an overload and breakdown of the system.

This particular fountain, I was told, is the only one that is still functioning from the original system

This system worked very well until it didn’t. Lack of maintenance and simply age caused a serious breakdown in the flow of water and its separation from waste.

The Medina is now served by a new water and sewage system, but there is more to be done.

Most every fountain in the Fez Medina has been replumbed and decorated with new tiles.

A thesis project by Harvard educated Moroccan, Aziza Chaouni, was to uncover the Fez River. The project won many awards and part of it has been realized. The project is called the River Remediation and Urban Development Scheme.

However, part of this is based on closing the tanneries, a very controversial subject as the tanneries are one of the primary tourists draws to the Fez Medina. The tanneries are a serious cause of the toxicity and pollution due to the chemicals involved, at the same time, the cleaning up of the Fez River is very important.

While the tanneries technically sit outside of the Medina, they are downstream from the town, so the river continues to flow through the tanneries to the valley. This water is then used for agriculture, making the toxicity from the tanneries an issue further down the line.

Just down from the photo above of the River Remediation Project, and just above the tanneries is this person throwing trash into the freshwater

Garbage Collection

On the plus side, Fez’s garbage collection is excellent. The city collects between 700 and 1000 tons of garbage every day. Waste collection also occurs every day of the week. Households put out their trash in various containers, then a man with a donkey comes, retrieves that trash and walks it out of one of the eight gates to a larger trash station. The walk must be a highly difficult one once the collectors start reaching the interior of the Medina and I imagine designing the collection route would be fascinating. Fez’s waste collection service, Ozone, employs 1,160 people and has an annual budget of 138 million MD (approximately $14 1/2 million US). Like everywhere in the world people still simply toss their trash into the streets, in the Fez Medina, however, there are employees who walk the streets during the day sweeping and collecting this trash.

Emergency Services

When world organizations gathered to work on the Fez situation they looked at the Medina, not as a resource, but rather as a bottleneck to modern urbanism. It lacked and still does, access roads for any form of emergency services, almost one-quarter of Fez el Bali (the older section of the Medina) is inaccessible by motorized vehicles. The company hired by the World Bank, in 1991, to produce a feasibility study, proposed cutting a large transportation swath through the historic district, many groups, led by UNESCO, objected and the bank rejected the proposal.

There is still no system. If a fire occurs, I am told people simply run.

However, if a sick person needs to be transported people gather together with donkeys, or carts or even their own hands to pass the person, through the quickest route, to an emergency vehicle outside the walls. There are volunteer groups, but also neighbors do help neighbors in these situations. This works for now, but the lifespan of the Moroccon people has increased significantly with good health care, and this lack of emergency services will definitely become a problem in the future. The Medina is also a highly unwelcoming space for anyone with the slightest handicap.

Police presence is another issue. While most Moroccans will tell you that you are safe as a tourist, and I agree with this, the streets of the Medina simply do not feel safe at night. There is no lighting, and most restaurants must offer porter services to walk you home as getting lost is so easy to do.

The most efficient type of transportation inside the Medina is the donkey

Sadly, the donkey is being replaced with wheeled carts that can be dangerous as their drivers go down the hills at rather high speeds yelling for everyone to get out of the way

Part of the Fez Medina restoration is these new workshops. You can see the open Fez River running through the middle of this project.

The opening up of the Fez River and building restoration just upriver from the Tannery

When walking in this area of the Medina, one can feel the overwhelming modernization and the lack of character.

Culture and Poverty

The rejection of the concept of cutting a swath of roads through the Medina changed the entire conversation regarding its future. UNESCO and the World Bank established a new goal of placing the cultural value of the Medina first with the goal of reducing poverty at the heart of the new proposal.

In the 1980s there was a severe drought in the countryside and many people moved into the Medina, as a result, the homes are overcrowded and 30% of the population lives below the poverty line.

What this newly stated goal actually means may be the reason very little has been done.

Commerce

Like so many places in the world, the merchants of the Medina need more imagination. An excellent example is the number of slipper salesmen. It is the mindset that, if my neighbor makes money that way, I must be able to make money that way. In the end, no one is making any money. There are a few fast food carts popping up, which are highly needed, especially for those working in the Medina. These were nice to see. More coffee shops where one could just sit and people watch would be even nicer, even the locals bemoan the lack of places to stop for coffee or tea.

However, everything one needs can be bought in the medina, including junk food.

School Supplies

Key making and even television sets

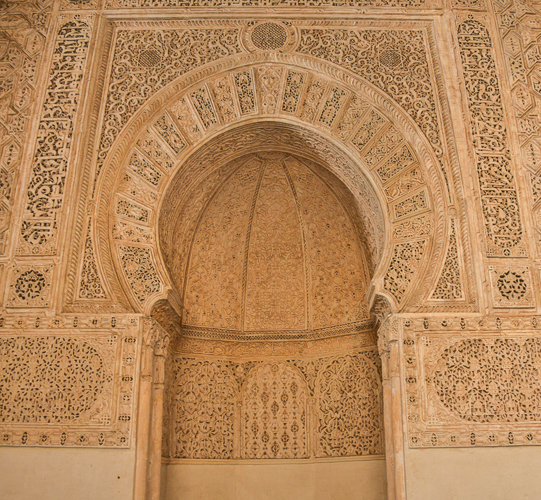

The Marrakech Medina in Comparison

The Marrakech Medina was added to the World Heritage list in 1985: “due to its impressive collection of monuments including the discernible Koutoubia Mosque, the splendid Ali ben Youssef Medersa and the opulent Bahia Palace. Within the ramparts are also numerous souks, hammams (public bath) and funduqs (caravansarai) that make Marrakech yet another Moroccan city where it pays to wander at leisure. And at the center of all this is Djemaa El-Fna, the city’s main square and a veritable open-air theatre with snake charmers, henna artists, and food vendors all vying for your attention.” (Description from UNESCO)

I will agree with the saving of the important monuments and the ramparts, but the Medina that I witnessed has the feeling of a large walled tourist destination. There are still sections on the edges where the poorer reside, but a good many of the homes have been purchased by foreigners (particularly the French) and are simply small hotels run from afar. As mentioned above this creates employment for local craftsmen, it has also resulted in a surge in property prices. With less accommodation available, locals are forced to move to distant neighborhoods or live in subdivided, often illegal buildings. Commercial rents in the medina have gone up as well

In a recent World Travel and Tourism Council report, Coping with Success, destinations were assessed using criteria including “threats to culture and heritage”, “alienation of residents” and “overloaded infrastructure”. Not quite as flooded with tourists as Venice or Barcelona, Marrakech is at a tipping point in terms of overcrowding and performed especially poorly in the “Negative TripAdvisor reviews” category. And yes, I realize as I write this, that I am a tourist, and therefore, automatically a part of the problem.

When you can buy fake Louis Vuitton covered footballs, you know you are in a ridiculously bizarre tourist shopping spot

There is no longer the feeling of a neighborhood, as there is in Fez. However, you can still get your laundry done, and buy your groceries, but the space allotted to these ventures aimed at locals is a very small fraction of the Medina, which is truly geared to selling, feeding, and entertaining outsiders.

The laundry service in the Marrakech Median even seems to be upscale from the hidden hole-in-the-wall laundries of other Medinas

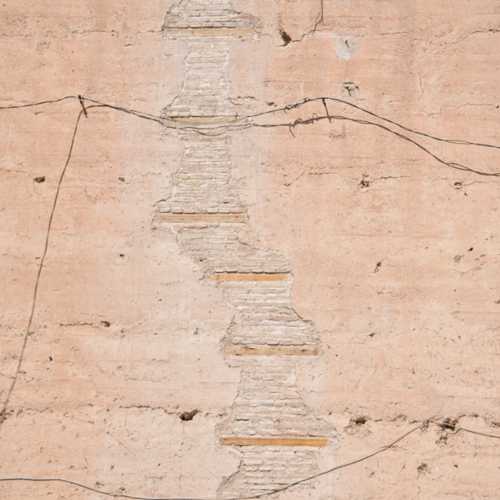

Saving the Ramparts and ancient walls of the Medina is listed as one of UNESCO’s highlights of preservation, and yet so many of the walls are crumbling to the point of destruction that they are being completely rebuilt, negating any historical value.

As I said when I began this post, these are not judgments, they are simply observations. I am still curious what the aim of UNESCO is in regard to this many Medina’s being placed on World Heritage Lists, which truly limits their ability to change, (for the good or bad).

I am a true believer in the protection of not only culture but history and the symbols of this history. I believe in preserving historically important sites, in fact, I feel that is more important now than ever, with the world weather and its effects in constant flux. Sadly, the situation of these Medinas is forcing people to either live in squalor or sell to an enterprising outsider to make a profit and change the character of the Medina. It is a circle that most likely does not have a satisfying answer.

An Aside

When I decided to go down this rabbit hole I hired a well-respected guide of the Fez Medina to walk and to talk. He was not completely sure what my goal was, but after an hour or so he understood what I wanted and began to open up. I won him over when after some amazing chickpea soup and lamb sandwich from a street vendor, I confessed it was the best meal I had had the entire time I had been in his country. The soup came from one vendor, the sandwich from another and we sat at the table in front of the guy who sold me the lemon juice to go with my meal. This is a true community. Even more interesting and telling, to me, when asked the price of the soup, the man simply said pay what you think it is worth, we insisted on paying the going rate of about $1 for a bowl of soup with bread.

Lemon juice, in this case, is lemon juice and mineral water. You add sugar to taste. This is called a Citron Presse in France.

My guide and I talked of preconceived notions and he told me a wonderful story of his understanding of America. He said when ATM’s first arrived, most Moroccans had no idea their purpose. This is true in many underdeveloped countries, the wealthy get it right away, but the less privileged don’t have bank accounts to even care what they are. He said Americans were so amazing, they put a card into a machine and their government just gave them money. I asked if he thought the streets of America were paved in gold and he sheepishly admitted that yes, when he was young he did.

Chickpea soup with a 1/4 inch of local olive oil on the top and local bread for slopping up the remains.

I complained that most every restaurant meal I had been served was entirely too many courses, too much food, and while Tajine is nice, it is not something I want every single day. He agreed, saying that the food of Morocco was so varied and wonderful, but Tajine is considered a food of status and something important to feed your guests, so if someone does not feed you Tajine they are not being a good host. I wish more restaurants would get away from the traditional tajine, so did he, he told me of a sandwich in the south of Morocco that sounded too good to be true, but alas, I will never know as restaurants don’t think foreigners want to be served such humble food.

You can find tajine absolutely everywhere

Morocco is a fascinating country, and its Medina’s are the heart of many of the most famous cities. It will be fun to watch how they evolve into the next century.

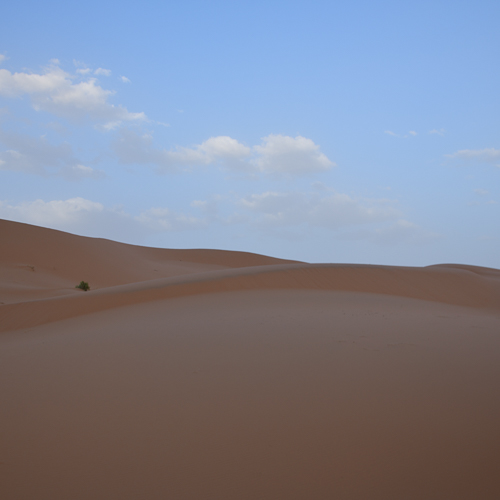

One of the most common types of construction in Morocco was rammed earth, an ancient building technique also known as “pies.” This type of architecture was once the primary form of architecture used in the Sahara Desert Region of Morocco.

One of the most common types of construction in Morocco was rammed earth, an ancient building technique also known as “pies.” This type of architecture was once the primary form of architecture used in the Sahara Desert Region of Morocco.

Stone

Stone

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*