November 2, 2022

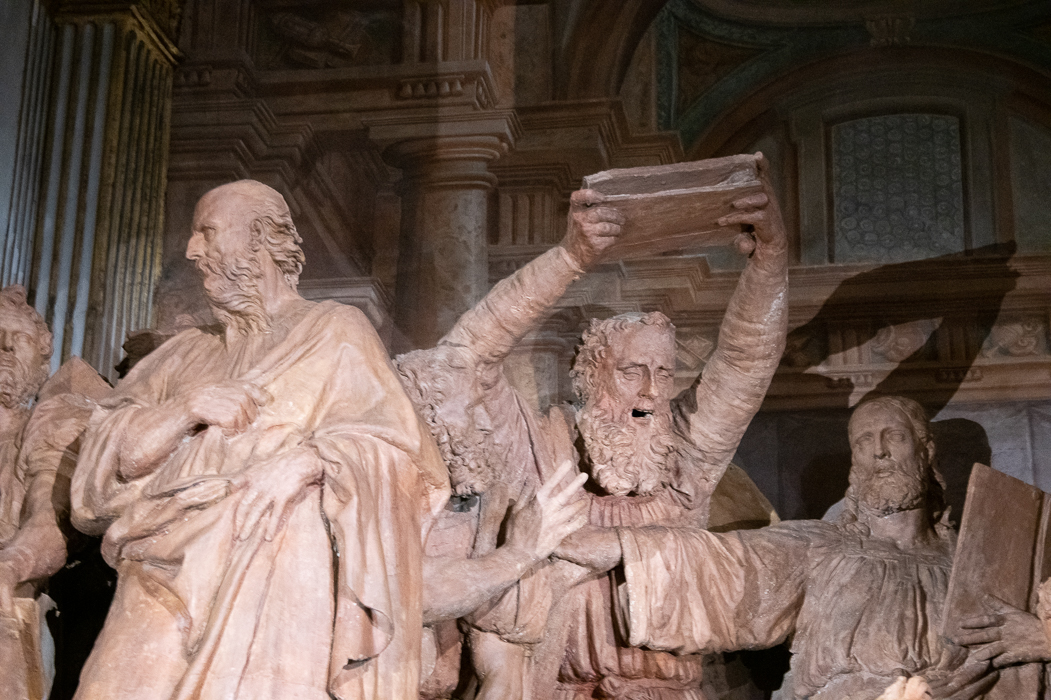

Il Campianto sul Cristo Morto by Niccolò dell’Arca 1463

Inside the Sanctuary of Santa Maria della Vita are two spectacular works of art in terra cotta.

First is the Il Campianto sul Cristo Morto (Lamentation Over Dead Christ) by Niccolò dell’Arca. This dramatic depiction of sorrow and death was commissioned by the brotherhood of the Battuti Bianchi around 1463 and consists of a group of life-sized figures, the Madonna and the Three Marys, St John the Apostle, and Joseph of Arimathea weeping over the dead body of Christ. Christ is laid out and ready for deposition in the tomb.

A 17th-century Emilian writer described them as the “endless weepers”. The piece is best described as a bold work for its time and restless synthesis of late-Gothic and Tuscan humanism, an art-historical diamond in the rough forever able to move, shake and seduce.

Christ lies at the center with his head reclining on a pillow. The most dramatic of the figures and the one that instantly draws your eyes is Mary Magdalen. Screaming in grief while her clothes appear to be blowing in the wind, she is traditionally shown at the feet of Christ for she was the sinner forgiven by him who had washed his feet and dried them with her hair. She is pictured here in the act of entering the Holy Sepulcher.

The next is Mary of Clopas (sometimes Cleophas ) shown in the act of keeping back the horror of the dead Christ with her hands and crying out her grief at the top of her lungs. She is traditionally identified as the wife of Clopas and as a relative of Mary, the mother of Jesus.

In the middle of the piece is St. John the Apostle, standing erect with his left hand under his chin. He seems to have a feeling of sadness and at the same time serenity.

Next is the Virgin Mary, the woman whose son lies in death before her. Her face appears, in my opinion, to express the greatest sense of grief.

To her left is Salome (mother of Santiago and Juan Evangelista), who appears to be holding back her pain and tears by clutching her legs with both hands.

The figure to the farthest left, kneeling and looking towards the observer is Giuseppe D’Arimatea. This is the man that asked Pilate for Christ’s body and provided a sepulcher for it. He was a wealthy man and faithful to Jesus, who bought the holy shroud and laid Christ’s body in the tomb he had set up for himself.

Little is known about Niccolo dell’Arca. The first mention of him was in September 1462 in Bologna as Maestro Nicolò da Puglia, a “master of terracotta figures”, most likely for this piece.

Other works of dell’Arca include the terracotta high relief of Madonna di Piazza (1478) on the wall of the Palazzo Comunale in Bologna. Some other important works include the terracotta bust of Saint Dominic (1474) (in the museum of the Basilica of San Domenico in Bologna), a marble statue of St. John the Baptist in Madrid, and the terracotta figure of Saint Monica (c. 1478-1480) in Modena.

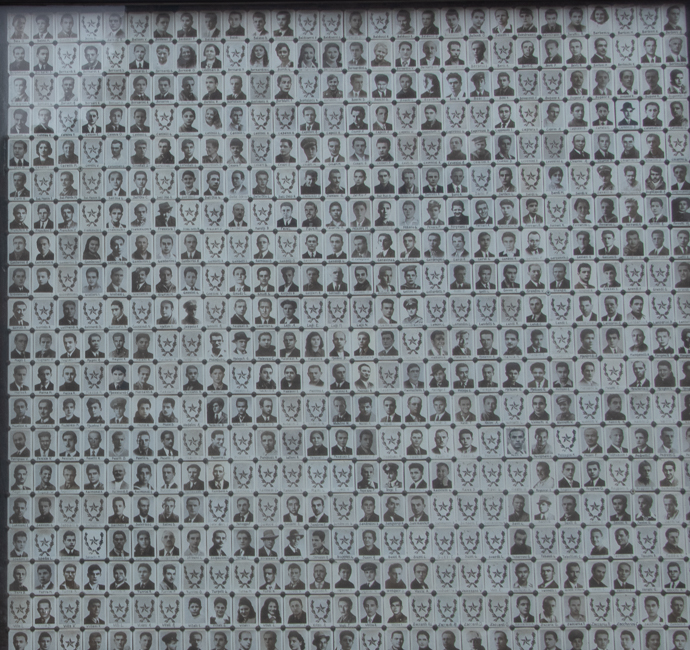

Transito della Vergine by Alfonso Lombardi 1519-1522

Transito della Vergine was commissioned for the oratory by the confraternity of Santa Maria Della Vita.

The subject was inspired by an episode of the apocryphal gospels, at the funeral of the virgin. A jew, who approached the coffin with the intention of profaning the body by tipping it over is thrown to the ground by divine intervention while an angel descends from heaven with his sword drawn for cutting off the hands of the profane. The whole scene pivots on the central figure of the jew. Crushed to the ground and surrounded by the twelve apostles depicted in various attitudes of anger rage and despair.

The use of terracotta for these images is historically important.

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire (c.450), the use of terracotta declined dramatically. The early Renaissance saw its revival as an artistic medium. Donatello and Lorenzo Ghiberti were among the first Renaissance sculptors to rediscover its potential for making Christian images, in particular, the Virgin and Child.

Clay was molded to replicate devotional images, and other figures, which were then fired, painted, and gilded, thus creating a low-cost alternative to more expensive materials, such as marble and bronze. Soon other artists, most notably, the Della Robbia family, popularized the use of glazed terracotta for relief sculpture and church altarpiece art.

Renaissance sculpture was responsible for reintroducing terracotta as a major medium for sculpture.