October 22, 2016

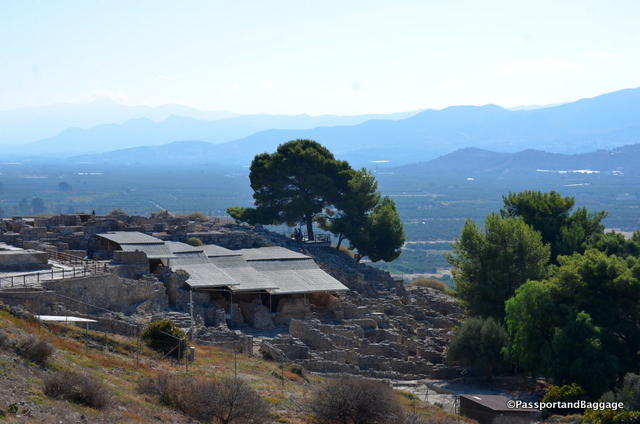

Heraklion is one the top of everyone’s list to visit when they go to Crete. The reason for this is Knossos. Knossos is crowded with tour buses pouring off of cruise ships, and tourists exploring on their own. The walk to the entry of the site is rampant with tchochke shops and barkers luring you in. It is one of those sites you must visit, so you put up with the scene.

In researching Knossos I came across an article by Joshua J. Mark, it is so excellently written that I am simply going to let your read his explanation, somewhat abbreviated for your ease in reading, and I’ll throw in my photographs with my personal observations.

In researching Knossos I came across an article by Joshua J. Mark, it is so excellently written that I am simply going to let your read his explanation, somewhat abbreviated for your ease in reading, and I’ll throw in my photographs with my personal observations.

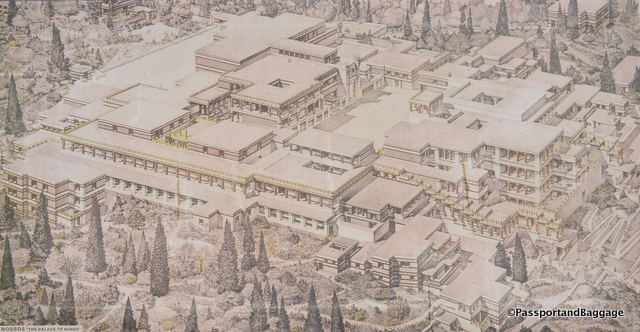

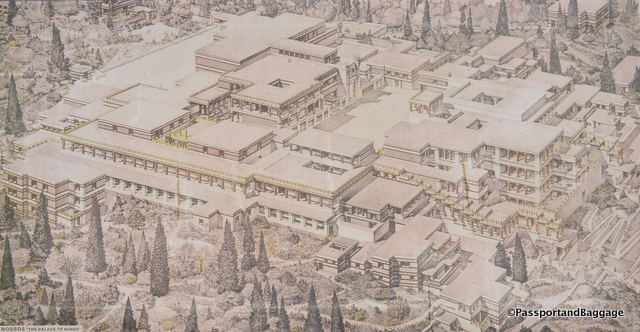

I found Knossos to be a real architectural wonder, the ability to build in such an elaborate manner, with four story buildings, in that time, is astonishing. This is an artists rendering of the site.

Knossos was told of by Homer in the Odyssey: “Among their cities is the great city of Cnosus, where Minos reigned when nine years old, he that held converse with great Zeus.” King Minos, famous for his wisdom and, later, one of the three judges of the dead in the underworld, would give his name to the people of Knossos and, by extension, the ancient civilization of Crete: Minoan.

Attitudes towards Evans’ reconstruction of Knossos among contemporary archaeologists are largely hostile – some regard his actions as tantamount to archaeological delinquency. But visitors – while pointing out that it’s not difficult to distinguish between original temple features and Evans’ restorations – will often argue that the reconstructed features are visionary in the way that they yield a unique and tangible insight into life inside the hub of Minoan culture, one that no mere ruins could ever offer. -From Archeology News Network

The settlement was established well before 2000 BCE and was destroyed, most likely by fire (though some claim a tsunami) c. 1700 BCE. Knossos has been identified with Plato’s mythical Atlantis from his dialogues of the Timaeus and Critias and is also known in myth most famously through the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. It should be noted that King Minos’ character in the story, as the king who demands human sacrifice from Athens, is at odds with other accounts of him as a king of wisdom and justice who, further, built the first navy and rid the Aegean sea of pirates.

The image of the bull is everywhere in Minoan art. You will find it in the Heraklion Archeology Museum on gold rings, terracotta figurines, stone seals, as well as frescoes.

According to the myths surrounding the early city, King Minos hired the Athenian architect, mathematician, and inventor Daedelus to design his palace and so cleverly was it constructed that no one who entered could find their way back out without a guide. In other versions of this same story it was not the palace itself which was designed in this way but the labyrinth within the palace which was built to house the half-man/half-bull the Minotaur. In order to keep Daedelus from telling the secrets of the palace, Minos locked him and his son Icarus in a high tower at Knossos and kept them prisoner. Daedelus fashioned wings made of wax and bird’s feathers for himself and his son, however, and escaped their prison but Icarus, flying too close to the sun, melted his wings and fell to his death.

The Minotaur, the monster-child of Minos’ wife, thrived on human sacrifice and Minos demanded the tribute of the noblest youth of Athens to keep the beast fed. Theseus of Athens, with the help of Minos’ daughter Ariadne, killed the Minotaur, freed the young people, and returned triumphant to his home city. Both stories cast King Minos in a very unflattering light while emphasing Athenian heroes which is unsurprising as they are considered Athenian in origin.

The throne room was unearthed in 1900 by British archaeologist Arthur Evans, during the first phase of his excavations in Knossos. This throne room is considered the oldest stone throne in Europe. The chamber contains an alabaster seat, identified by Evans as a “throne”, while two Griffins rest on each side staring at it. What fascinated me the most were the three sides with gypsum benches.

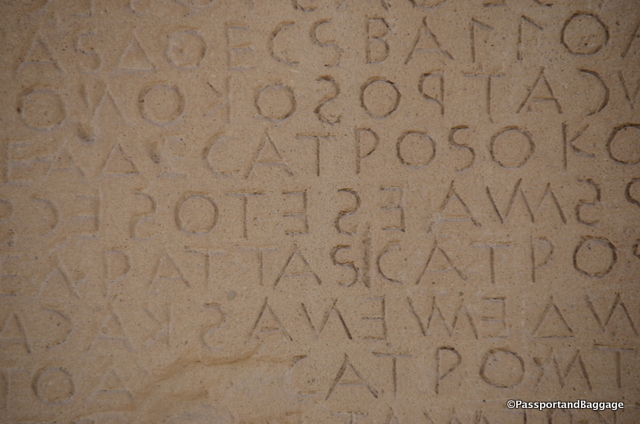

The first palace identified in modern times was built c. 1900 BCE on the ruins of a much older settlement. As the writing of this period, so-called `Cretan Heiroglyphs’, has not been deciphered, nothing is known about this time save what can be discerned through archaeological evidence.

This first palace was destroyed c. 1700 BCE and re-built on a grander, though less massive, scale. The city of Knossos, and almost every other community center on Crete, was destroyed by a combination of earthquake and the invading Mycenaeans c. 1450 BCE with only the palace spared.

This first palace was destroyed c. 1700 BCE and re-built on a grander, though less massive, scale. The city of Knossos, and almost every other community center on Crete, was destroyed by a combination of earthquake and the invading Mycenaeans c. 1450 BCE with only the palace spared.

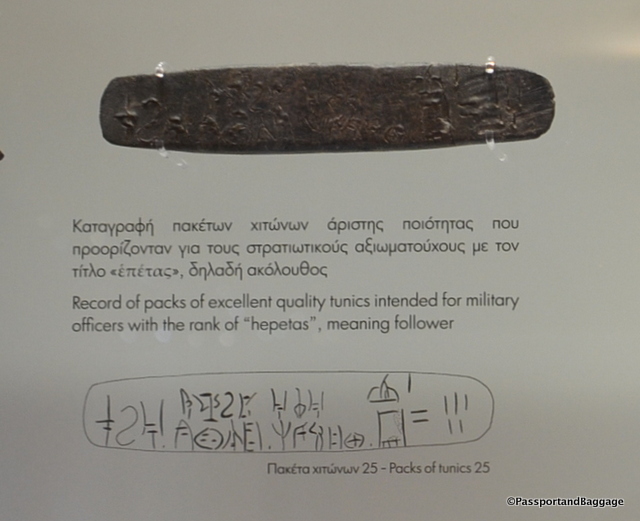

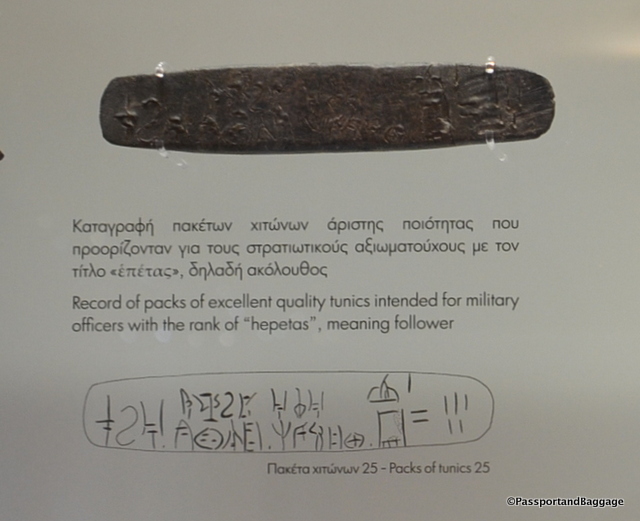

The eruption of the volcano on the nearby island of Thera (Santorini) in c.1600 or 1500 BCE has long been held a major factor in the destruction of the city and second palace. Recent scholarship, however, argues against this theory citing Mycenaean activity at the palace after 1450 BCE. The Mycenaen writing system, known as `Linear B’, continues in Crete after the eruption of the Thera volcano and there is further evidence that the Mycenaens re-built the damaged palace. In fact, it appears that Knossos became an important base of operations and capital of the Mycenaeans until it was destroyed by fire and finally abandoned c. 1375 BCE. The date which traditionally marks the final end of the Minoan civilization is 1200 BCE after which there is no evidence for the culture.

Examples of Linear B found at Knossos, now in the Heraklion Archeology Museum

“Horns of Consecration” is a term coined by Sir Arthur Evans to describe this ubiquitous Minoan symbol. It represents the horns of the sacred bull. These limestone horns are restorations, but others made of stone or clay were placed on the roofs of buildings, tombs and shrines, probably to show the sanctity of the building.

The Horns of Consecration of various sizes, found in the Archeology Museum of Heraklion

For centuries, Knossos was considered only a city of myth and legend until, in 1900 CE, it was uncovered by the English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans and excavations were begun.

Through frescoes on the walls, the excavated site revealed more about the Minoan sport of bull jumping and the ancient story of Theseus and the Minotaur (half-man-half-bull) seemed more probable than fanciful.

The story of the labyrinth also was given more credence once the intricate interior of the palace was uncovered. It was Evans who first called the ancient inhabitants of Crete ‘Minoan’ after King Minos of Knossos, and his efforts in excavation and re-construction, however controversial, paved the way for all future work in both physical and cultural anthropology concerning the Minoan civilization. – Joshua J. Mark (excerpted)

The geology of Knossos also fascinated me. This is a large piece of gypsum stone. We also saw huge ashlar blocks of local sandstone and limestone.

Fresco secco, which is the application of paint, in particular for details, onto a dry plaster was used throughout Knossos as was the use of low relief in the plaster to give a shallow three dimensional effect.

Pithoi were manufactured all over the Mediterranean. They were used for storing or shipping wine, olive oil, or various types of vegetable products. They became known as pithoi when western classical archaeologists adopted the term to mean the jars uncovered during excavations of Minoan palaces on Crete.

These beautifully painted pithoi are in the Heraklion Archeology Museum

There are highly interpreted re-creations of the frescoes found during the original excavation. The original fragments are in the Archeology Museum in Heraklion.

*

*

Water technologies included running water within the palaces drainage systems, piping systems, rainwater harvesting, and other technologies.

The site is ringed with trees where you can step away from the blistering heat in the center, yet it was still very warm, even in October. It takes around 2 hours to explore the site properly. At present it costs €16/person and that lets you into the Archeology Museum as well.

A must, after Knossos is to visit the Archeology Museum of Heraklion. The museum is world famous for its Minoan art collection.

Here you will learn about more details of everyday life. I have always been fascinated with the death rituals of societies around the world, the Minoan’s buried their people in what are called Larnakes. Larnakes, plural of larnax are small closed coffins or “ash-chests”. If not cremated, the deceased was placed in a fetal position, perhaps, signifying the return to the beginning of life, then the larnakes were placed in tombs.

The larnakes were beautifully ornamented in the same style as frescoes.

A larnake in the Archeology Museum of Heraklion

These symmetrical double-bitted axe are called Labrys. Originally from Crete they are some of the oldest symbols of Greek civilization. The Labrys is most closely associated in historical records with the Minoan civilization and specifically with the worship of a goddess. In Crete the symbol always accompanies female divinities.

I have always loved the whimsey in pottery from ancient civilizations. These pieces are representative of the Rhinoceros Beetle, the black ones are actual beetles.

Immense cooking pots

Obviously palaces require large cooking vessels to feed huge crowds, these are much larger than they appear in the photos, and rather impressive to behold.

One has to truly appreciate the fact that the shopping bag has been around since the beginning of time.

Regarding the museum, you need a minimum of one and one-half hours for a visit, two would be best. The museum is laid out perfectly, it walks you in a logical manner and takes you through chronologically. In the end there are two private collections bought from well known collectors and then a sculpture gallery.

The project was designed by Renzo Piano with the intent to give the view back to the people. It is a giant sloping park that leads to a single building that holds both the National Library and the Opera House with a public area called the Agora, between the two buildings.

The project was designed by Renzo Piano with the intent to give the view back to the people. It is a giant sloping park that leads to a single building that holds both the National Library and the Opera House with a public area called the Agora, between the two buildings.