December 30 2018

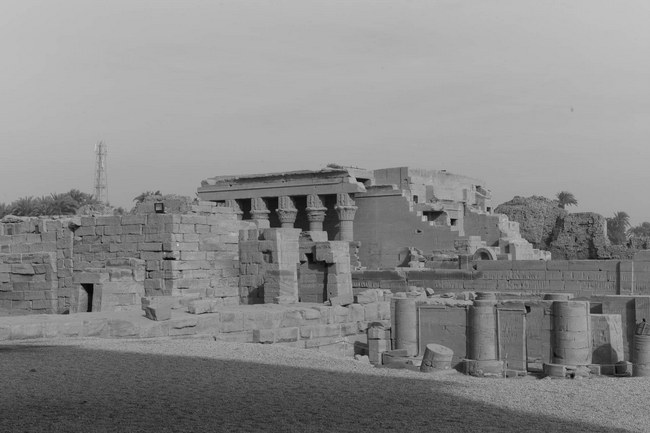

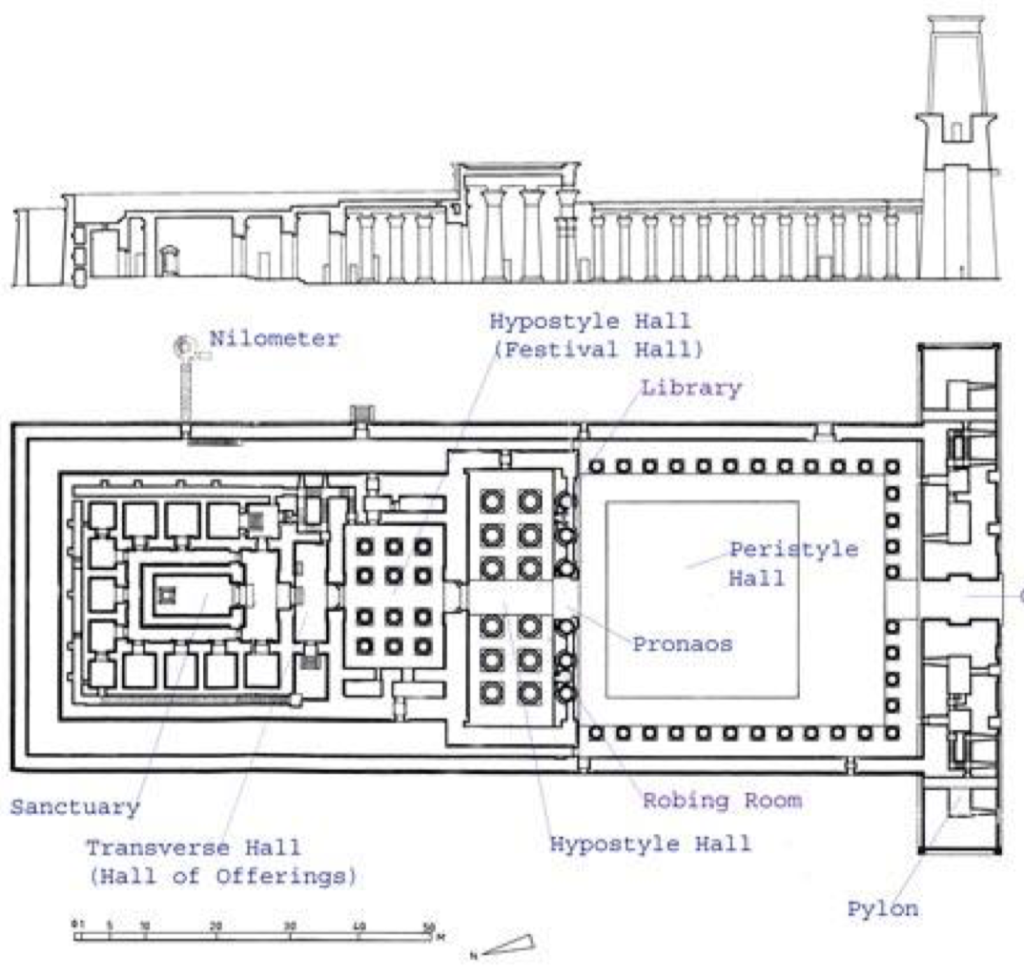

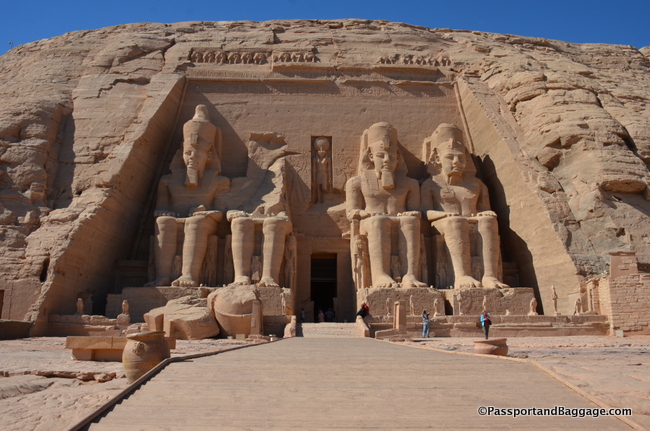

If I were to do this trip over I would begin in Luxor. This is the seat of all that Egypt embodies in its ancient history, and starting here might have helped me put the dynasties into a more comprehensive order. While understanding the exact order of history is not completely necessary since every era is built upon the other, it might have helped me put a few things in perspective.

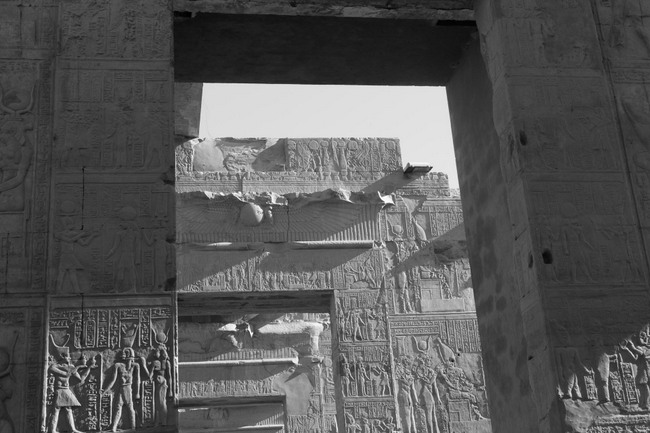

The natural pyramid that looms over the Valley of the Kings is why it was chosen as the burial site for the Egyptian kings of the 16th to 11th century BCE

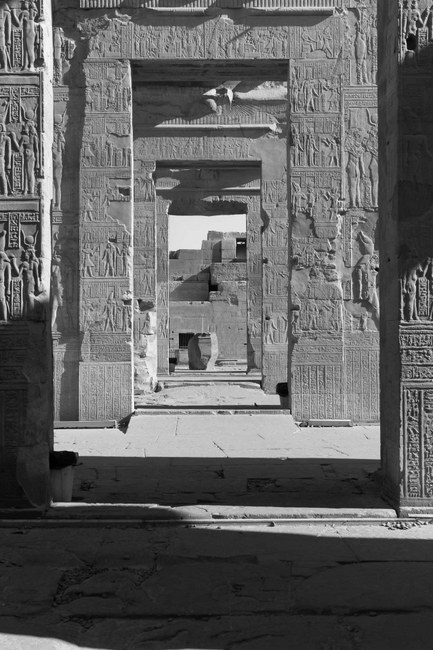

My first stop in Luxor was the Valley of the Kings. This sits on the west bank of what is now Luxor, but at the time was called Thebes.

Life occurred on the east bank of the Nile and death on the West Bank, this all had to do with the rising and setting of the sun.

Ancient Egypt was ruled by the God Ra, the deity of the sun. Everything is determined by the path of the sun, including these burials.

One of my favorite symbols of Egypt is the Scarab, not to detract from its holiness, but in many countries, it is known as the dung beetle.

The Scarab symbolized the sun, the ancient Egyptians correlated the rolling of the dung with the rolling of the sun across the sky.

The scarab was also a symbol of immortality, resurrection, transformation, and protection and can be seen in much of the funerary art. The life of the scarab revolves around the dung balls that they consume, lay their eggs in, and feed their young, all this represented a cycle of rebirth to the Egyptians. When the eggs hatched the scarab beetle would seem to appear from nowhere, making it a symbol of spontaneous creation, resurrection, and transformation.

Iconography showing the scarab pushing the sun in front of him across the sky in the tomb of Setnakt in the Valley of the Kings.

Scarabs with spread wings were a symbol of extended protection.

Scarabs with spread wings were a symbol of extended protection.

This scarab sculpture at the Temple of Karnak in Luxor dates to the reign of Amenhotep III. Karnak is not its original location: it may have belonged to the mortuary temple of Amenhotep III and was moved to Karnak under King Taharqa of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.

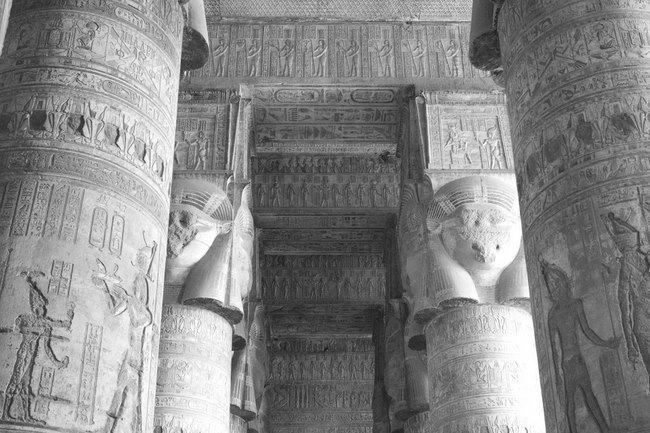

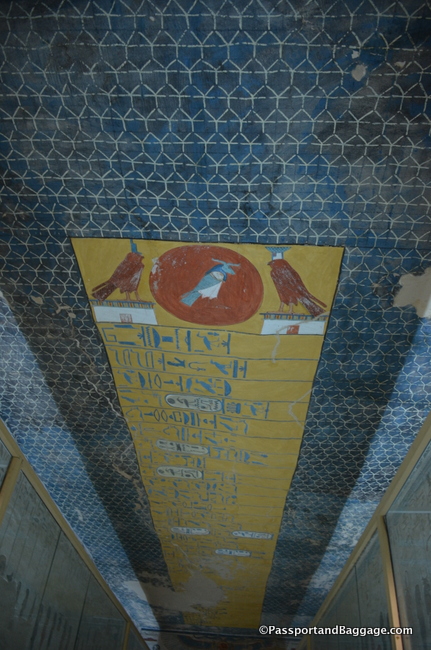

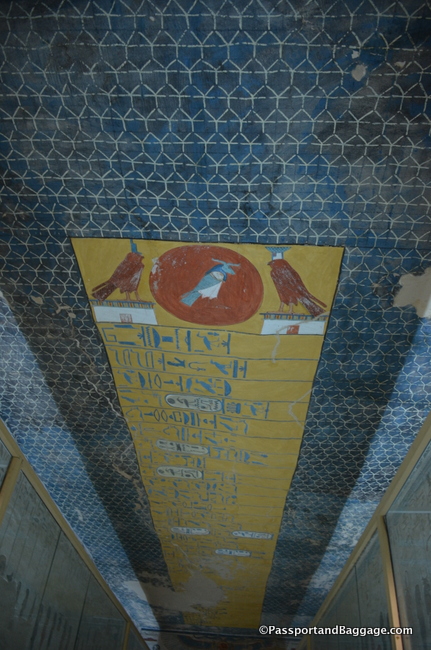

Another representation of the sun seen in many sites is the goddess Nut. Nut was the mother of Osiris, Isis, Seth, and Nephythys, and is usually shown in human form; her elongated body symbolizing the sky. Each limb represents a cardinal point as her body stretches over the earth. Nut swallowed the setting sun (Ra) each evening and gave birth to him each morning. Most often you will find her on the ceilings of tombs and temples and on the inside lid of coffins.

You can see Nut inhaling the sun and then it shows again at her feet (in this depiction at her belly) in the morning to begin the day anew. – The Tomb at Abydos.

Nut on the roof of the Tomb of Ramses IV

The ticket to the Valley of the Kings gives you entry to 3 tombs. There are approximately eleven open tombs whose viewing schedules are rotated to give the tombs a rest from the visitors. The air and water in a humans exhalation are damaging to the paintings in the tomb.

The tomb of Tausert/Setnakt

In many tombs, you will find the snake Apep or Apophis. He was the god of chaos and while he was indestructible his body had to be cut into pieces before you could leave the underworld and return.

The tombs all have numbers Tomb KV14 is said to be the final resting place of Tausert and Setnakht. Due to having two complete burial chambers, KV14 is also one of the largest tombs in the valley. Queen Tausert reigned from 1220-1215 BCE. Setnakht, the first pharaoh of the twentieth dynasty (1189 BCE to 1186 BCE), took over Tauserts tomb and altered much to suit himself.

Tomb of Siptah in the Valley of the Kings

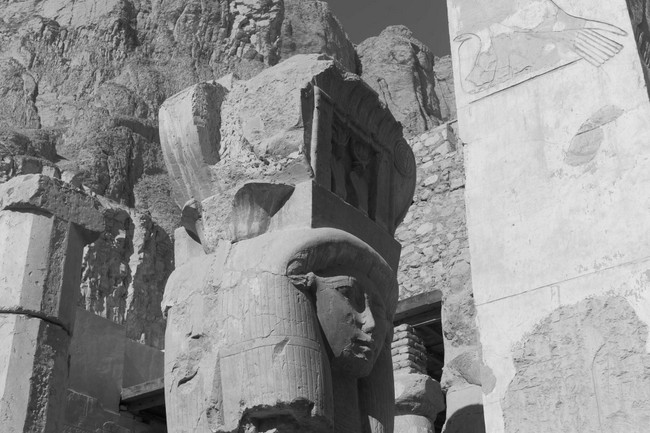

Amazing images of the ceiling of Siptah’s tomb show Nekhbe. The patron of Upper Egypt and one of the two patron deities for all of Ancient Egypt when it was unified.

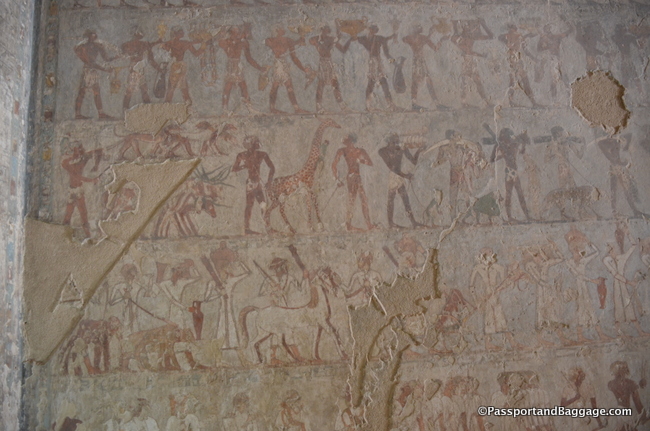

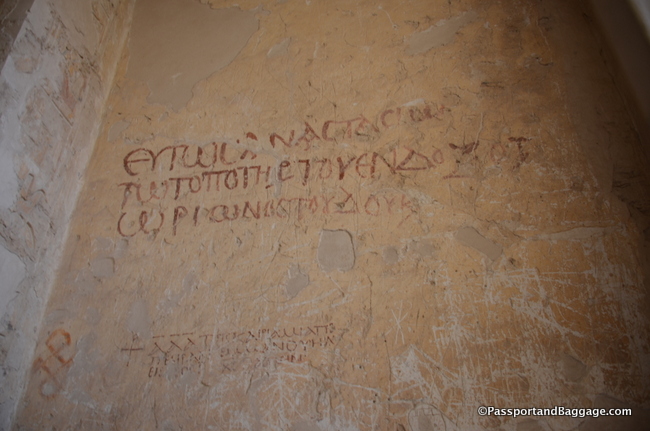

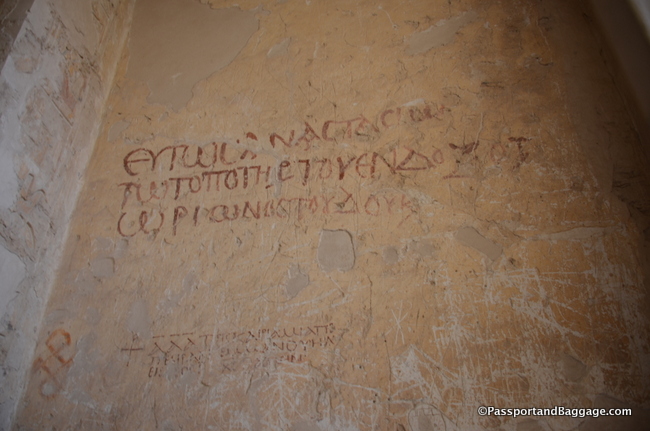

The tomb of Ramses IV was unique for two things one finds inside. First is the inscription left by Coptic and Greek priests when they lived in the tombs and second is the language used along the walls.

Coptic language of priests

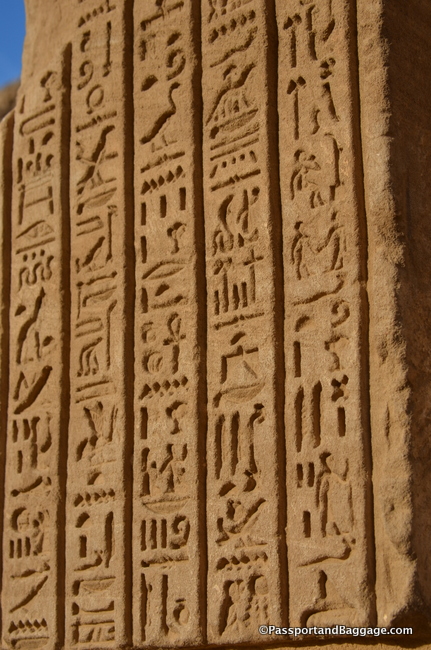

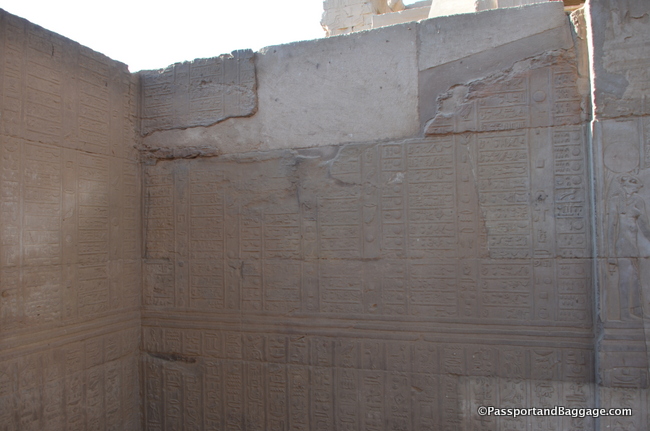

The language is not hieroglyphics but the hieratic script, a cursive form of hieroglyphics used mainly by the priests.

Hieratic script

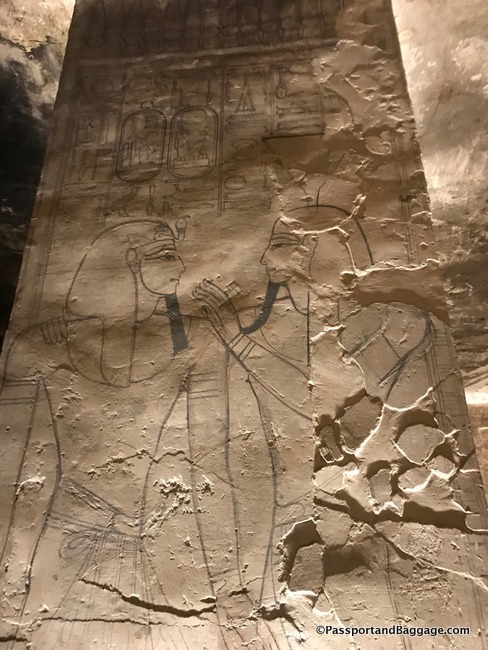

A small indication of the artwork inside the tomb of Ramses IV

I paid an additional $100 to visit the Tomb of Seti I and the Tomb of Tutankhamen. The Tomb of Seti 1 was absolutely worth every dime, the colors are so vivid and different than any other temple, as well as the etchings. The Tomb of Tutankhamen is interesting in the fact that it was never finished, but what was finished, was spectacular. No photographs are allowed in either of those tombs.

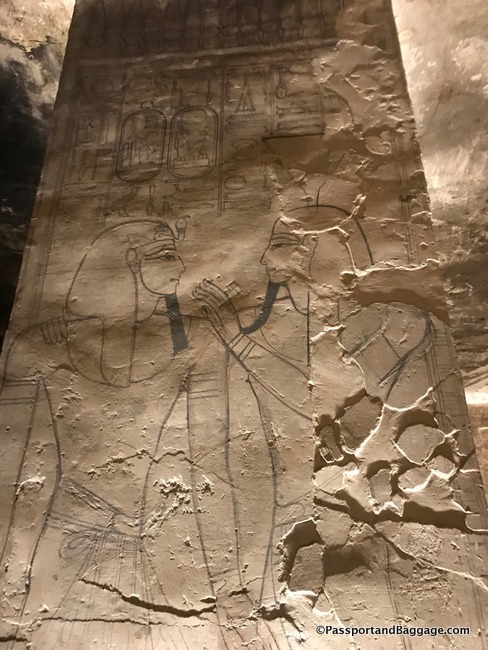

As I mentioned photos were not allowed in the two tombs I paid extra to visit. I did, however, attempt to take photos with my phone, as everyone else in the tomb was doing. I got caught and it was not a pleasant experience. For this reason, I did not even consider it in the tomb of Tutankhamen. Here are the shots I captured in Seti I tomb.

*

*

*

* *

*

The tomb was not finished so some walls still simply have the drawings that would later be carved and painted.

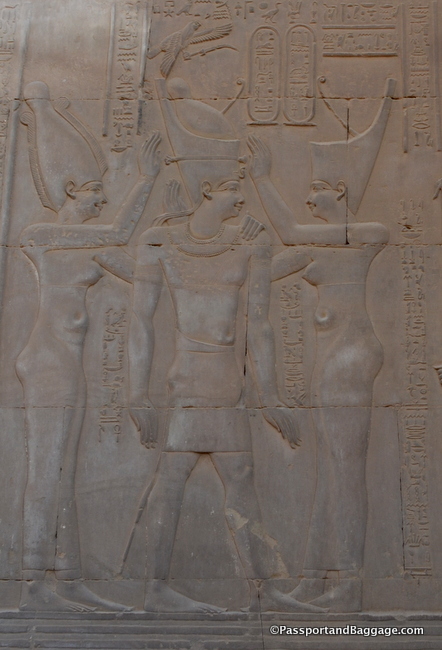

One of the reasons I wanted to take photos is that the reliefs in the Seti I tomb were different than anything else I had seen, all the figures and hieroglyphics in Seti I’s tomb are sculpted in basso-relievo and then painted. The final photo in an unfinished chamber.

The block walls were made as smooth as possible, and where there were flaws in the rock it was filled with a cementitious filling. The area would then be covered with a plaster coating. The first sketches were done in red, later, what some guides said were the priests, but my instinct is it was probably a lead, and higher skilled artist, made corrections in black.

The sculptor then cut out the plaster around the lines giving the figures the appearance of being raised off of the wall rather than etched in. This was the way the tombs were done from the 18th dynasty onward.

Giovanni Battista Belzoni the discoverer of the tomb, in discovering the tombs said this in 1820: “When the figures were completed and made smooth by the sculptor, they received a coat of whitewash all over. This white is so beautiful and clear, that our best and whitest paper appeared yellowish when compared with it.”

(I was told by one guide that they were covered in egg whites, while highly possible, that would be a lot of eggs.)

Each color used in the paintings was created by mixing various naturally occurring elements and each of these colors became standardized in time in order to ensure uniformity in the artwork. An Egyptian male, for example, was always depicted with a reddish-brown skin which was achieved by mixing a certain amount of the standard red paint with standard brown. Variations in the mix would occur in different eras but, overall, remained more or less the same. This color for the male’s skin was chosen for realism, in order to symbolize the outdoor life of most males, while Egyptian women were painted with lighter skin (using yellow and white mixes) since they spent more time indoors.

The colors and how they were made is a long and interesting story which you can read more of here.

The Valley of the Kings from above

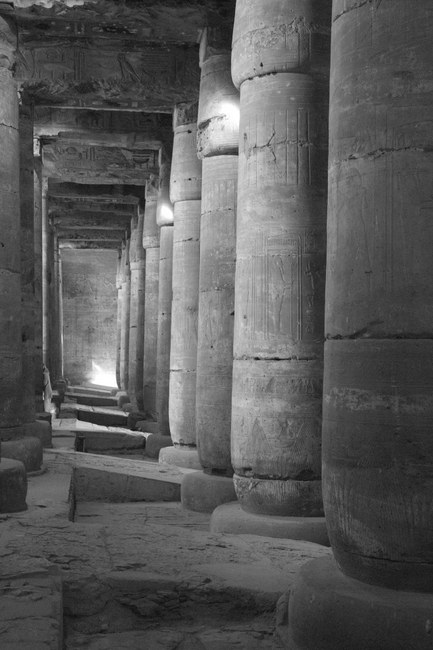

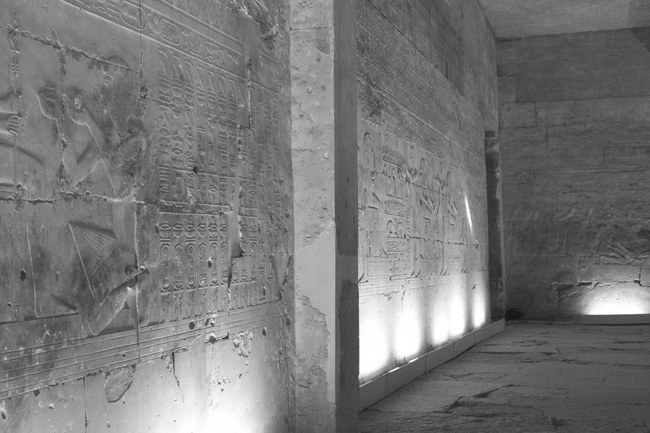

Photography is always tough in a dark tomb, made worse by the crowds I encountered in some as well. Here are a few that I hope will give you an idea of the magnificent artwork you encounter.

Goddess Isis in the Tomb of Tausert and Setnakt

The ceiling in the tomb of Tausert and Setnakt

The tomb of Ramses IV