November 18, 2019

Carthage is not at all what this author expected. It is far larger than one can comprehend, and yet the ruins lay scattered amongst a vibrant, very wealthy part of Tunisia.

Most people are introduced to Carthage through books 1 through 4 of Virgil’s Aeneid and this alone was my greatest reason for wanting to explore this area of the world.

A quick and very simplistic recap of The Aeneid:

Aeneas is destined to found Rome. As he and his entourage near their destination, a fierce storm throws them off course and lands them in Carthage. They are all heartily welcomed by Dido, Carthage’s founder, and queen.

On the first night, Aeneas spends a long dinner recanting the tales of the sack of Troy that ended the Trojan War.

He then tells how he escaped the burning city with his father, Anchises and his son, Ascanius and after the loss of his dear father Anchises and a slew of terrible weather, they found themselves in Carthage.

Dido is impressed by Aeneas’s exploits and sympathetic to his suffering, as she, Dido, a Phoenician princess had fled her home and founded Carthage after her brother murdered her husband. Dido, sadly, falls in love with Aeneas. They live together as lovers for a period until the gods remind Aeneas of his destiny. He is determined, despite his knowing that he will break Dido’s heart, to set sail once again. Dido is devastated by his departure and orders the building of a huge pyre with Aeneas’s castaway possessions. Dido climbs upon the pyre and stabs herself with a sword Aeneas had left behind.

Then there is the recorded history of Carthage that is just as full of plot twists, cunning, and intrigue. I ask the forgiveness of historians, for this cryptic, incomplete summary of the great history of Carthage.

Who were the Carthaginians, and if I understand that will I understand the rest of Tunisian history? Well…it is a start.

Carthage was founded as a Phoenician colony, ostensibly by Dido.

The Phoenicians were a maritime trading nation, they were originally drawn to northern Africa as staging posts for the long haul across the Mediterranean.

While these ports date back to 1100 BCE, Carthage dates to around 814 BCE, as mentioned by Virgil, founded by Queen Dido, who, in history is also known as Queen Elissa. The people that found their way to Carthage were a band of nobles exiled from their Phoenician homeland.

The society of Carthage was dominated by an aristocratic trading class who held all of the important political and religious positions, but below this strata was a cosmopolitan mix of artisans, laborers, mercenaries, slaves, and foreigners from across the Mediterranean. The city’s population at its peak was somewhere around 400,000.

The aristocracy of Carthage was not based on land ownership but simply wealth. Indeed, this was a criticism of Aristotle when commentating on Carthage – that such a preoccupation with wealth would lead inevitably to a self-interested oligarchy dominating society.

Aristotle was correct. This desire for money above all else meant that when needed, the cantankerous money-grubbing Carthaginians had no allies to help in defending their territory.

There were problems on the horizon when the Greeks began to expand in the seventh century BCE.

However, when the Romans began to supersede the Greeks in both Sicily and Italy, Carthage had a formidable opponent.

The Roman desire for this territory gave us the THREE Punic wars.

(The name Punic comes from the word Phoenician as applied to the citizens of Carthage, who were of Phoenician ethnicity. As the history of the conflict was written by Roman authors, they labeled it ‘The Punic Wars’.)

The first, 263-251 BCE, was majorly a naval skirmish around Sicily. Carthage lost the war and had to accept Roman terms. These included surrendering its fleets and agreeing to accept influence by and to pay war debts to Spain (Hispania). A side note, Hannibal’s father was a leading Carthaginian commander during the First Punic War.

The Carthaginians then turned their attention to Spain. The Carthaginian general Hannibal crossed over the agreed border in 218 BCE and began his legendary march, elephants and all, through France and over the Alps. Eventually, Hannibal was tied down in Italy and forced to return to Carthage. He was defeated at the Battle of Zama by the Roman Scipio Africanus. Hannibal eventually fled to what is now Turkey where he maintained a reputation as a dreaded and respected opponent. Carthage had to once again relinquish its fleet and this time agree to never train elephants.

The Romans continued to feel threatened by Carthage, despite these two victories. Senator Cato the Elder, also known as Cato the Censor, Cato the Wise, and Cato the Ancient, was a Roman soldier, senator, and historian who ended each of his speeches in the Senate with “Carthage must be destroyed”.

In 150 BCE a third war resulted in the complete sacking of Carthage. The historic descriptions are particularly gruesome. Ruins were plowed under and the proverbial salt was poured into the furrows to ensure the fields remained barren.

Carthage was gone and eventually, the Romans moved in.

In 46 BCE Julius Ceasar refounded Carthage where it grew to be the second city of the empire with an estimated population of between 400,000 and 700,000 people.

As Carthage’s Roman moral and military foundations began to crumble the Christians began to have a say. St. Augustine said of Carthage “Up to very recently those effeminates were walking the streets and alleys of Carthage, their hair reeking with ointment, their faces painted white, with enervate bodies moving along like women, and even soliciting the man on the street for sustenance of their dissolute lives.”

The Vandals and Byzantines attempted to keep Carthage alive but Arab invaders did a rather thorough job of destroying Carthage once again, hauling away most everything for buildings elsewhere in what we now call Tunisia.

An aside, as it is not fair to throw in two previously undiscussed cultures.

The Vandals were a “barbarian” Germanic people who settled in Carthage making it their capital for about a century. They remained in Carthage until it succumbed to an invasion force from the Byzantine Empire in 534. The Vandals successfully sacked Rome in 455 CE proving Cato had not been wrong about the risk of an enemy on the shores of Northern Africa.

The Byzantine Empire was often called the Eastern Roman Empire or simply Byzantium and existed from 330 to 1453 CE. They lost Carthage to the Arabs in the 7th Century CE.

It has been difficult to excavate Carthage, first thanks to the Romans complete destruction of the original city and the fact, that what was left by the Romans was carted away by the Vandals and the Arabs. Then in modern times, it was buried under the modern city of Carthage.

These are stelae in the Tophet, a sacred enclosure where the Punic people offered sacrifices especially of young children in honor of the protective divinities of Carthage, Baal Hammon, and Tanit. While remains of children have been found, it is doubtful the number of sacrifices were as large as Roman propagandists wanted the world to believe.

The Punic port is now a meager pond. The only way to understand what was once the glory of Carthage are the models on the small island in the center of the pond. One of the models shows the island as one big shipyard.

Byrsa Hill was the heart of Carthage under Punic rule. While the homes were close together, they were as tall as 5 stories each with their own cistern. The scorched remains found at the foundations show the Rome did indeed burn Carthage to the ground. The distance of Byrsa Hill from the Sea is only a small indication of how large Carthage was.

On Byrsa Hill is the Cathedral of Saint Louis, dedicated to the French King Louis IX who died in Carthage while laying unsuccessful siege to Tunis in the hopes of converting a Hafsid (Sunni Muslim) ruler. “Instead of a proselyte, he found a siege”

The house known as the “villa of the aviary”, was restored to provide a reconstruction of the inside of an African Roman villa.

A view from the Villas Romaines giving one a perspective of how far they are from the port and how large Carthage was. The Villas were halfway between Byrsa Hill and the port.

The Antonine Baths are the vastest set of Roman Thermae built on the African continent and one of the three largest built in the Roman Empire. The baths are also the only remaining Thermae of Carthage that dates back to the Roman Empire’s era. The baths were built during the reign of Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius and sit on the beach of Carthage.

* *

*

A Punic Funerary Chamber 5-6th Century BCE in the area near the baths

Sidi Bou Said

A delightful respite from the walking and mind-bending history of Carthage is a trip up into the mountains to the city of Sidi Bou Said with its very high-end hotels, restaurants, and shopping.

A delightful respite from the walking and mind-bending history of Carthage is a trip up into the mountains to the city of Sidi Bou Said with its very high-end hotels, restaurants, and shopping.

The town is named after Abu Said Ibn Khalef Ibn Yahia El-Beji, a Muslim saint who spent much of his life studying and teaching at the Zitouna Mosque in Tunis. The village’s original name was “The Fire Mountain”, and referred to the beacon that was lit up on the cliff to guide ships working their way through the Gulf of Tunis.

In the 1920s the town adopted its blue and white color scheme inspired by the palace of Baron Rodolphe d’Erlanger, a famous French painter, and musicologist known for his work in promoting Arab music, who lived in Sid Bou Said from 1909 until his death in 1932.

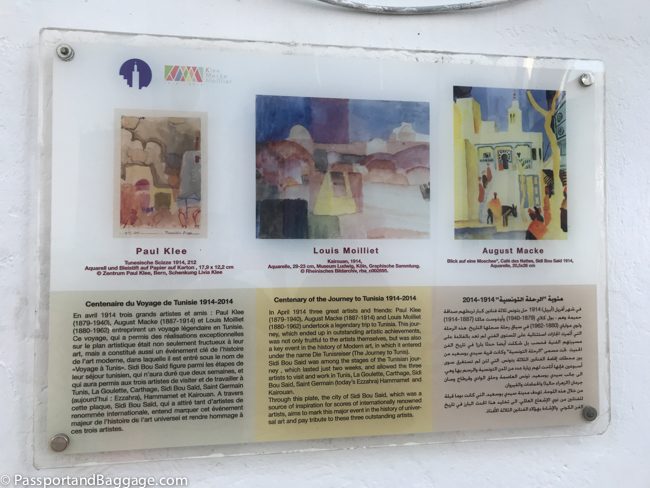

Sidi Bou Said has a reputation as a town of artists. Artists who have lived in or visited Sidi Bou Said include famous occultist Aleister Crowley, Paul Klee, Gustave-Henri Jossot, August Macke and Louis Moillet. Tunisian artists in Sidi Bou Said are members of École de Tunis (painting school of Tunis), such as Yahia Turki, Brahim Dhahak and Ammar Farhat. French philosopher Michel Foucault lived there for a number of years while teaching at the University of Tunis. French author Andre Gide also had a house in the town.

A glass of wine in Sidi Bou Said

Tunisia has a long but turbulent history of winemaking. The production of wine in the area dates back to around 814 BCE during the Punic era. Ancient Carthage was known for its wine production and was in fact home to the world’s first documented viticulturist – Mago (or Magon). Mago was an agronomist who wrote a long guide to agronomy and viticultural practices in Ancient Carthage sometime before 146BCE. When the Romans sacked Carthage, they stole Mago’s book and took it to Rome, where it was translated from Punic to Greek and Latin, fragments of which still exist today. Mago’s book included advice on how to plant and prune vines, where to plant, according to the topography of the land (it was his suggestion to plant on north-facing slopes to protect vines from the heat of the African sun), and how to make wine. The Phoenicians and the work of Mago were instrumental in developing the Roman and Ancient Greek culture of winemaking, which spread across Europe some centuries later.