October 2021

Azulejos were originally Moorish, then Spanish, and later a Portuguese art form. These tiles have been produced since the 14th century.

At first, the term was used to denote only North African mosaics, but it became the accepted word for an entirely decorated tile about 5 to 6 inches square.

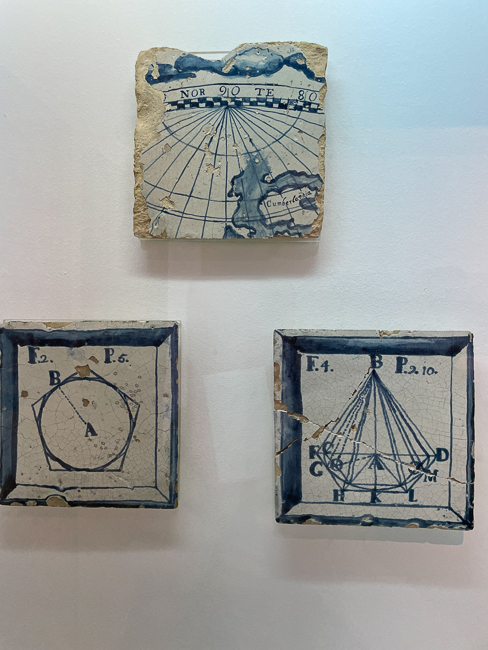

Azulejo comes from the Arabic word az-zulayj, meaning “little stone” or “polished stone.” The Moors painted their tiles in Arab-influenced zellige style, using amazingly elaborate geometric patterns adhering to the Islamic tradition of ornamentation devoid of human figures.

At the Monastery of São Vicente de Fora. An unbroken tiled pattern winds throughout the entire monastery, from the entranceway and across the gallery to the indoor hallways and atriums. A total of around 100,000 tiles were used, making it the world’s largest collection of Baroque tiles.

The industry grew popular in Lisbon around 1550 when immigrating Flemish artists began experimenting with the art form. This was during the reigns of Philip II, III, and IV when Portugal was struggling to become independent of Spain. Spain virtually ceased to manufacture them by the 18th century.

Portuguese exports of tiles to the Azores, Madeira, and Brazil began in the 17th century. Azulejos produced in Puebla, Mexico, later became the tile of this art form that most westerners are aware of.

Initially, one-colour versions of the tiles were used in Portugal in decorative chessboard patterns.

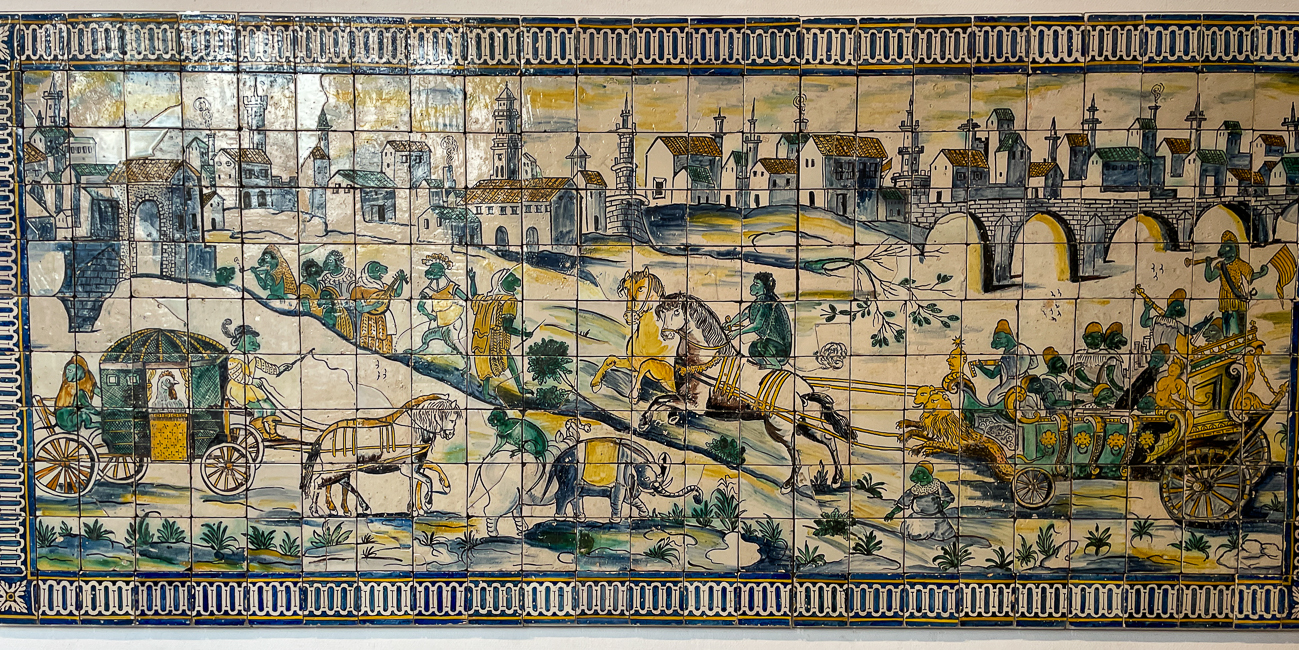

Eventually variations began to include polychrome designs;

Then they began to include scenes with military or religious themes;

Some of my favorites were ridiculously fun singeries (French for Monkey Trick) which depicted monkeys in human roles.

The use of ridiculous depictions of mythical beings also added a touch of whimsey to many of the pieces.

The Museum of Azulejo sits inside the Madre de Deus Convent, founded in 1509 by Queen D. Leonor. The elements of the church were breathtaking, and the murals religiously interesting.

The earthquake of 1755 did a lot of damage to the grand buildings covered in Azulejos that one associates with Portugal.

The use of continuous blue tiles, accented with blue balconies is a real attention getter in the narrow streets of the Santa Cruz neighborhood. This simpler style of tile is called pombalinos after the Marquis of Pombal, who was responsible for the rebuilding efforts after the 1755 earthquake.

The tile below is a closeup of the tiles that cover the house you see in the photo below.

The tile below is a closeup of the tiles that cover the house you see in the photo below.

Found in the Chiada section of Lisbon, this building dates from 1863, it’s completely covered in mostly yellow and orange tiles with images representing Earth, Water, Science, Agriculture, Commerce and Industry. At the top is a star with an eye in the center, symbolized the Creator of the Universe.

The best way to see a vast collection of tiles and receive a valuable education is to visit both the Museum of Azulejos and the Monastery of Saint Vincent de Fora.

Above is just one of the 38 panels that make up part of the Monastery of Sao Vicente de Fora collection. These panels are the fables of La Fontaine, created by master Policarpo de Oliveira Bernardes between 1740 and 1750. Jean de La Fontaine was a French fabulist and one of the most widely read French poets of the 17th century.

In the Azulejo Museum I fell in love with the above tile. It was by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905). Born in Lisbon, he is one of the most well know tile artists of his time.

In the Azulejo Museum I fell in love with the above tile. It was by Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905). Born in Lisbon, he is one of the most well know tile artists of his time.

In the Azueljo museum is a 75 foot long tile panoramic view of Lisbon prior to the 1755 earthquake. This small section above, where you can see smoking chimneys was the neighborhood of Mocambo, where many of Lisbon’s potteries were located. The district today is called Madragoa, a term that in Umbundo means small village, place of refuge. This is the area where a significant part of the population was once freed slaves.

In the Azueljo museum is a 75 foot long tile panoramic view of Lisbon prior to the 1755 earthquake. This small section above, where you can see smoking chimneys was the neighborhood of Mocambo, where many of Lisbon’s potteries were located. The district today is called Madragoa, a term that in Umbundo means small village, place of refuge. This is the area where a significant part of the population was once freed slaves.

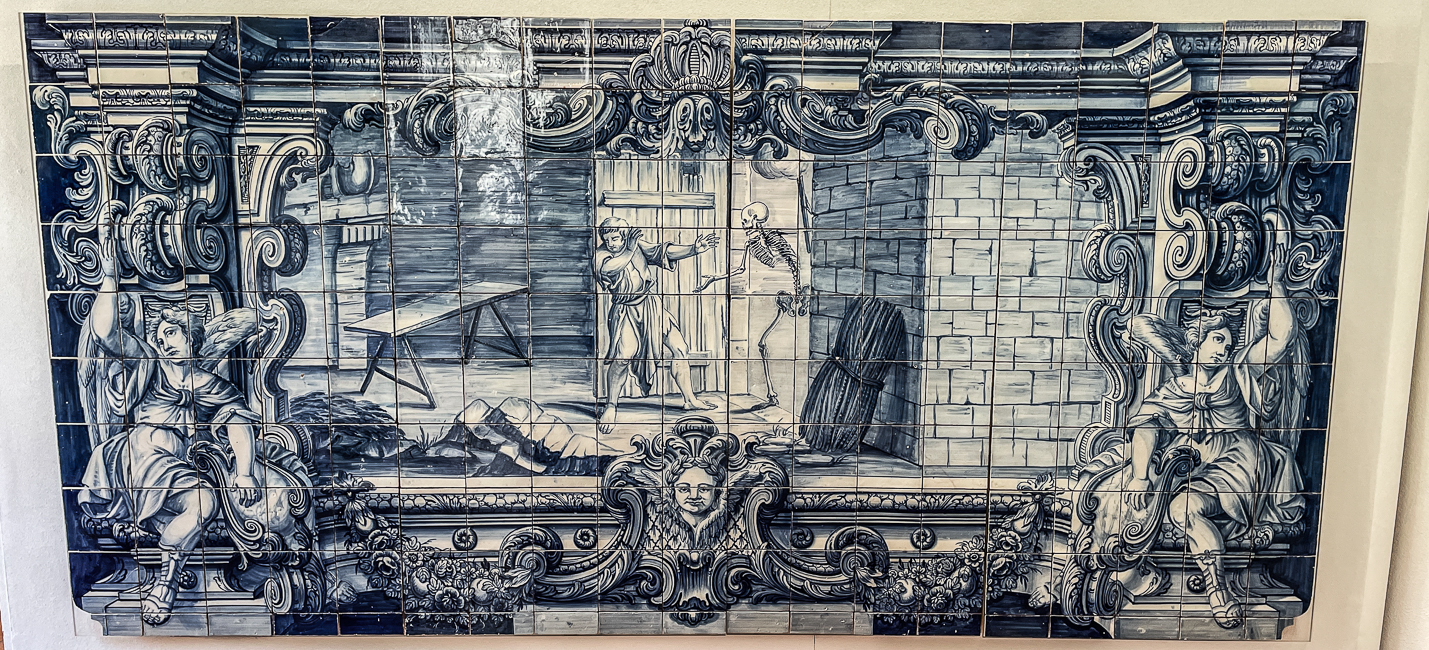

At one time is was a fad to copy etchings. This Image was based on the engraving “Mars” from the series “Twelve Months” by Henri II Bonnart, Paris c. 1678

Walking down one of the narrow alleys of the Santa Cruz neighborhood I spotted this.

Walking down one of the narrow alleys of the Santa Cruz neighborhood I spotted this.