October 21, 2016

Phaistos

The day began by visiting Phaistos, an important site of the Minoan civilization. The Minoan civilization, which flourished in Crete during the second millennium BC, ranks among the great civilizations of the ancient world. It had four places of power, areas that are called palaces, Knossos, Phaistos, Mália and Zakros.

The lands they chose were rich in agriculture and had direct access to the important sea routes of the time.

These sites were not, as we think of palaces, just residences of royalty. They were the seats of administration and justice, thriving commercial and manufacturing centers and trading centers.

The architecture of these “palaces” was influenced from the East, the common characteristic being the rectangular central courtyard.

These palaces, though destroyed throughout time, were rebuilt after each disaster. They existed for about 600 years.

There were two major architectural phases at both Phaistos and Knossos; the Early Palaces, which were destroyed in around 1700 or 1650 BC, possibly due to earthquakes, and the New Palaces, built on the same sites that eventually suffered damage around 1450 BC, the reason for this has many theories and is still debatable.

Phaistos was also an important city-state of Dorian Crete (1100 BC). The Dorian’s were one of the four major ethnic groups among which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece considered themselves divided (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ionians). They are almost always referred to as just “the Dorians”, as they are called in the earliest literary mention of them in the Odyssey.

Phaistos was the second largest and second most important of the four major towns. The reason to visit Phaistos, is that, unlike Knossos, no reconstruction has taken place.

Górtyn

The Saint Titus Basilica in Gortyn, dedicated to St. Titus, the first Bishop of Crete, and was erected in the 6th century AD

Just a few miles from Phaistos in Górtyn, one of the mightiest city states in Dorian Crete (1100 BC). It was here, according to legend, that Zeus, transformed into a bull, carried the princess Europa on his back from her home in Phoenicia. It is said that the sacred marriage was contracted beneath the evergreen plane tree beside a brook in Górtyn. It is told that the tree still exists today. A colossal statue of Europa sitting on the back of a bull was discovered at the amphitheatre in Górtyn in the nineteenth century and is now in the British Museum.

Górtyn has a rich history. It is where Hannibal sought refuge after his defeat by Antiochos, and it helped the Romans conquer Crete, which is why it was not destroyed by Quintus Metellus, unlike Knossos. According to Book III of Homer’s The Odyssey, Menelaus and his fleet of ships, returning home from the Trojan War, were blown off course to the Górtyn coastline. Homer describes stormy seas that pushed the ships against a sharp reef, ultimately destroying many of the vessels but sparing the crew. The city was eventually destroyed in 825 AD by the Arab invasion, which formed the Emirate of Crete, a Muslim state that existed on Crete from the late 820s to the Byzantine reconquest of the island in 961.

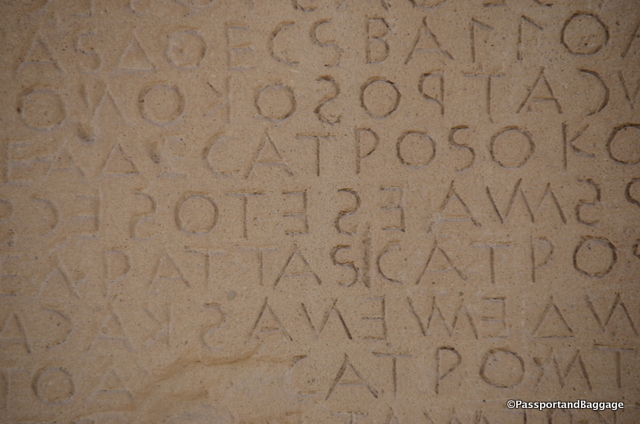

Housed behind the Odeon is The Górtyn Code, discovered in 1884, it is both the oldest and most complete known example of a code of ancient Greek law. The code was discovered at the Odeon, a structure built by the Roman emperor Trajan.

The code dates from around 500 BC. Each stone contains 12 columns of inscriptions in a Doric Cretan dialect. There is a total of 600 lines which read alternatively from left to right and from right to left, a style known as boustrophedon, literally, “as the ox plows”. The laws were on display to the public and related to domestic matters including marriage, divorce, adoption, the obligations and rights of slaves and the sale and division of property.

Spinalónga

We ended our day in a seaside restaurant in the town of Pláka, looking out to the island of Spinalónga. Originally Spinalónga was not an island – it was part of the island of Crete. During Venetian occupation the island was carved out of the coast for defense purposes and a fort, with a large protective wall, was built there, the remains of which can still be seen.

The island was subsequently used as a leper colony from 1903 to 1957. It is notable for being one of the last active leper colonies in Europe. The last inhabitant, a priest, left the island in 1962. This was to maintain the religious tradition of the Greek Orthodox Church, in which a buried person has to be commemorated at following intervals of 40 days; 6 months; 1 year; 3 years; and 5 years, after their death.

Today it is a deserted, however it remains a popular tourist destination with boats leaving many of the towns that surround it, every ½ hour. This is due to the fact that it was featured in the British television series Who Pays the Ferryman? and Werner Herzog’s experimental short film Last Words. It is also the setting for the 2005 novel The Island by Victoria Hislop. Our hotel clerk said people arrive clutching the book and anxious to take the trip out. It is not on my agenda, although I have read the book.

A walk around Pláka shows what an upscale town it has become after a very large, unattractive, high-end resort was built right on its outskirts.

The history of Crete is so very complicated, I have gotten lost in the telling many times. If you are interested here is a link to a timeline of the history of the island.